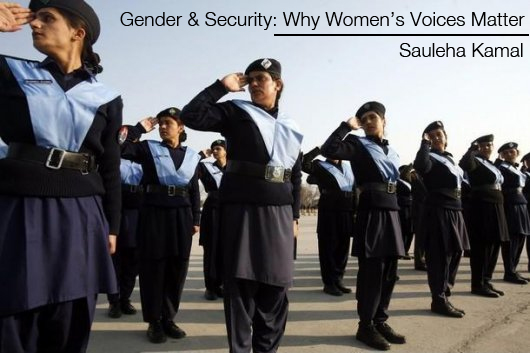

Gender & Security: Why Women’s Voices Matter

- by: Sauleha Kamal

- Date: April 15, 2016

- Array

This October, it will be sixteen years since the United Nations adopted Security Council Resolution 1325 affirming the importance of women in peace negotiations, peace-building and post-conflict reconstruction. Despite this, security policy continues to effectively ignore women both as peacemakers and conflict affectees. This is extremely dangerous; perhaps nowhere more than in Pakistan, where conflict worsens an existing gender imbalance. In this age of splintered militancy, Talibanism and a fast-creeping Da’esh presence, the state more than ever before needs security policy to be clear and robust, and red lines on women’s rights etched in stone.

Conflict affects women differently than it does men. As the monopoly of violence increasingly shifts towards soft civilian targets post-2014, it is imperative that security policy address these differences. Though the majority of combatants are men, more women die from indirect effects of conflict, including, but not limited to, women’s rights rollbacks, social order breakdowns, inadequacy of health provisions and economic devastation[i]. A domestic environment of inequality—and increased sexual violence—is also strongly correlated to state militarism, and gender inequality is a reliable predictor of armed conflict.

So far, counterterrorism measures have not pursued long-term peace or extended beyond the “male” domain of guns and warfare. Not only are robust deradicalisation measures missing from Pakistan’s 20-point National Action Plan, the six deradicalisation programs currently running also virtually ignore women and gender-specific effects of conflict[ii]. The NAP, which has been criticized for its implementation and dismissed as more of a “wish list” than a functional plan of action, does not even address overt militant agendas of curtailing the visibility and rights of women in KPK, FATA and South Punjab.

While policymakers may be leaving women out of the security conversation, militant groups are decidedly not. Last year, the Khansaa Brigade, the women’s wing of Da’esh, disseminated a manifesto “Women in the Islamic State”. Here in Pakistan, between 1998 and 2003, militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba released a three-volume book “Ham Ma’en Lashkar-e-Taiba,” featuring a gaudy cover with a bloodied pink rose, to inspire support for violent jihad among women. Notably, though not surprisingly, such groups claim to protect women’s rights but do nothing to curtail violence against women, domestic or otherwise; arguably, accelerating its incidence instead.

Women’s rights, freedoms and mobility are some of the first casualties of militant take-overs. In conflict-hit FATA, which is governed by Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR), disputes are often resolved before all-male jirgas that have been known to reduce women to commodities. Peace deals with militants have already adversely affected women: In 2009, the Nizam-e-Adl concession to Taliban heavily curtailed women’s rights with the imposition of a Talibanized brand of sharia in Malakand.

That conflict means the loss of male relatives for many women spells worsening economic conditions that, in this traditionally patriarchal society,leave women dependent on often-abusive extended families. Armed conflict also increases the incidence of domestic violence: According to one FATA researcher, now “when a woman is killed, you can just blame it on the Taliban or the paramilitary depending on what side you’re on”[iii]. Meanwhile, persistent militant threats make parents reluctant to let daughters attend school. The situation for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) is all the more troubling: Female IDPs are particularly vulnerable to trafficking; high male mortality rates in conflict areas mean that many IDPs—who have lost male family members—manage female-headed households, yet, compensation packages fail to account for their unique financial difficulties; concerns about purdah in camps severely limit women’s mobility and access to food; finally,camps lack infrastructure for adequate reproductive healthcare[iv].

One major barrier in the way of inclusive security is that movements for women’s inclusion and/or rights are conflated to Western cultural imperialism more often than not. Foremost amongst opposition to Punjab’s Protection of Women Against Violence Bill were Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl Chief’s remarks that he would not let Pakistan become a “Western state”. Such sentiment obscures the simple fact that the West does not have a monopoly on women’s empowerment, nor should it. Historically, Pakistan has not been a nation that wants to see women sequestered but a nation standing on the shoulders of women who refused to be sidelined. Women from Fatima Jinnah and Begum Jahanara Shahnawaz to Benazir Bhutto have eviscerated tropes of what postcolonial theorist Gayatri Spivak termed “white men saving brown women from brown men”. It is evident that we have the capacity to “save” ourselves on our own terms. All that’s needed is consistent will.

For this, policymakers need to adopt a more comprehensive approach that acknowledges the linkages between security and women’s rights. To establish a peace that is lasting, not transient, we must incorporate gender equality goals into security discussions and include women in peace negotiations.When included in peace negotiations, women bring up different priorities, steer conversation towards building a lasting peace and address underlying humanitarian problems. This is essential to the future of security. It is imperative that we first ensure women’s rights are protected, then, work on including women in the security conversation. The latter shouldn’t be hard to do in a country that ranks high on the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s list of women in national parliaments.

A good start would be to discuss gender-sensitive policy and remain cognizant of attempts by non-state actors to clamp down on any women’s rights guaranteed by our constitution. Finally, as militant groups increasingly involve women in radicalization, we must involve women in deradicalisation at the community level too. It is about time we took a more inclusive approach to human security and made sure that gender equality policies extend beyond CEDAW checklists and tokenisms.

[i] https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/IPI-E-pub-Reimagining-Peacemaking.pdf

[ii] Project Sparley is the only known deradicalisation program that even extends its efforts to families.

[iii]http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/asia/south-asia/pakistan/265-women-violence-and-conflict-in-pakistan.pdf

[iv]http://pakistansocietyofvictimology.org/Userfiles/Gendered%20Perceptions%20and%20Impact%20of%20Terrorism.pdf

____________________________________________

Sauleha Kamal is Project Officer, SSI at Jinnah Institute. She tweets @Sauliloquy1

Please note that the views in this publication do not reflect those of the Jinnah Institute, its Board of Directors, Board of Advisors or management. Unless noted otherwise, all material is property of the Institute. Copyright © Jinnah Institute 2016