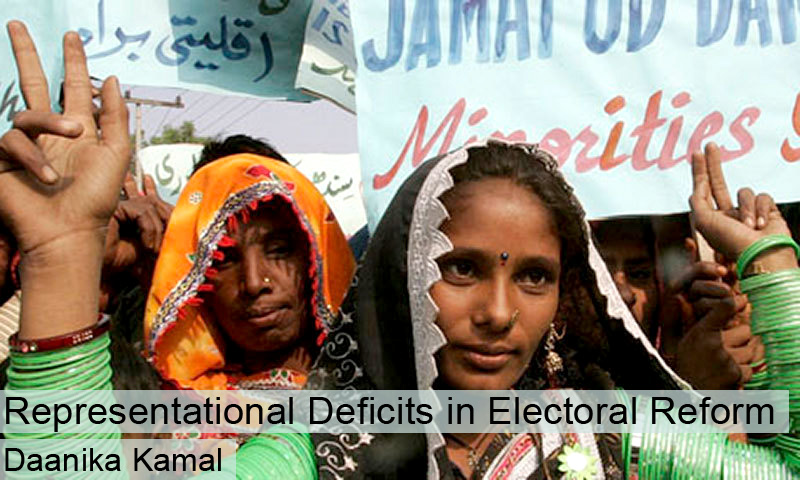

Representational Deficits in Electoral Reform

- by: Daanika Kamal

- Date: April 19, 2016

- Array

A functional democracy requires public ownership of the electoral process. In Pakistan, making these processes inclusive of women, persons with disabilities and minorities is even more important. The recently released report on the Election Commission of Pakistan’s(ECP) Second Five Year Strategic Plan states that the Commission’s objectives relating to minority participation in electoral systems have been “achieved in letter and spirit.”Despite this proclamation, progress on ground remains stymied, as the ECP has failed to meet demands for direct election and has been unable to advance minority representation in electoral reforms.

Introduced in 2014, the ECP’s Second Strategic Plan is premised on the identification and consequent rectification of electoral issues. Goal 9 focuses on ‘ensuring participation of minorities in electoral process’ by developing culturally sensitive materials for electoral education, advancing training modules for political participation of minorities and conducting training workshops with officials to reiterate ECP’s ‘guiding principle’ of inclusiveness. Goal 12 specifies the need for at least five percent of ECPs workforce constituting minorities. These goals are ambiguous at best. “Ensuring the participation of minorities” without specifying ‘how’ the objective is to be achieved makes it difficult for one to evaluate success.

The Citizens Report on ECP’s progress studied plan-based development initiatives to find that the Commission had reported no progress with respect to minority participation. It also noted that ECP planned on meeting over 75 percent of their objectives by the end of 2015, however no attempt to manage inadequacies in their organizational structure has been accounted for. ECP’s efforts to include minorities in ‘letter and spirit’ are therefore very much restricted to the former. As a result, minorities continue to be invisible in electoral reforms due to lack of representation in political parties, separate voting lists, inequitable voting rights and an indirect election process.

Worryingly, the indefinite postponement of the Census means that accurate information denoting the proportional allocation of seats in federal and provincial legislatures continues to lack. Since 1985, reserved seats for minorities in the National and Provisional Assemblies remained unchanged, despite a 30 percent increment in overall seats, illustrating the symbolic rather than political purpose ‘reserved’ seats serve. It was not till early March 2016 that the National Assembly Standing Committee on Law and Justice made a decision to take forward an amendment proposed by Asiya Nasir in 2014, a Christian member of parliament, which calls for increasing the number of reserved seats for minorities in the National Assembly from 10 to 15 and adds 6 seats in Provincial Assemblies to be distributed accordingly. This however, is not an initiative undertaken by ECP.

In political discourse, opportunities for minorities are limited to reserved seats in assemblies where a lack of direct elections retains them at a representational disadvantage. Recruitment is based on nominations submitted by political parties in proportion to seats secured by the respective party during general elections. This indirect process used to fill assemblies was implemented in 2002 without prior consultations with minorities. Those elected rarely represent a minority group, and their allegiance typically lies with their political party. With the exception of Pakistan Peoples Party’s recent resolve to give general tickets to candidates from minority communities in Sindh (based on a proportional representation system), demands for a direct election process remain largely unmet by the ECP.

Individuals from minority groups that choose to contest elections independently are typically confronted with societal discrimination. For example,in the 2013 elections, a Hindu candidate faced locally distributed leaflets labeling all Hindus as ‘infidels’ and accordingly admonishing Muslims from voting in their favour. Similarly, Ahmadis continue to be unaccounted for in the common list of voters in Pakistan, registered instead on publically available separate voter lists specifying their religious identity. Given their already perilous position in society, many Ahmadis choose to boycott elections to secure themselves from possible threats resulting from list-based identification.

What is required now is a proactive attempt to integrate minorities into the political system. Political parties need to allocate resources for the preparation and advancement of candidates representing minorities and should advocate intra-party elections for a more transparent and robust process. Education for voters and candidates alike will not be effective unless the ECP makes materials and training schedules accessible to all, with content that specifically covers matters related to minorities. Considering that the mismanagement of elections in 2013 came after majority of ECP’s First Strategic Plan was implemented, the Commission will have to enable itself to be more efficient this time around. Self-proclaimed achievements listed in ECP-issued progress reports,without any publically available documents supporting their apparent implementations will undoubtedly raise suspicion in all matters overshadowed by the Commission. Affirmative action must be taken in order to incite an incremental process of electoral reform, especially with respect to minorities.

____________________________________________

The writer works for Jinnah Institute. Twitter: @daanikakamal

Please note that the views in this publication do not reflect those of the Jinnah Institute, its Board of Directors, Board of Advisors or management. Unless noted otherwise, all material is property of the Institute. Copyright © Jinnah Institute 2016