Twitter Cafe

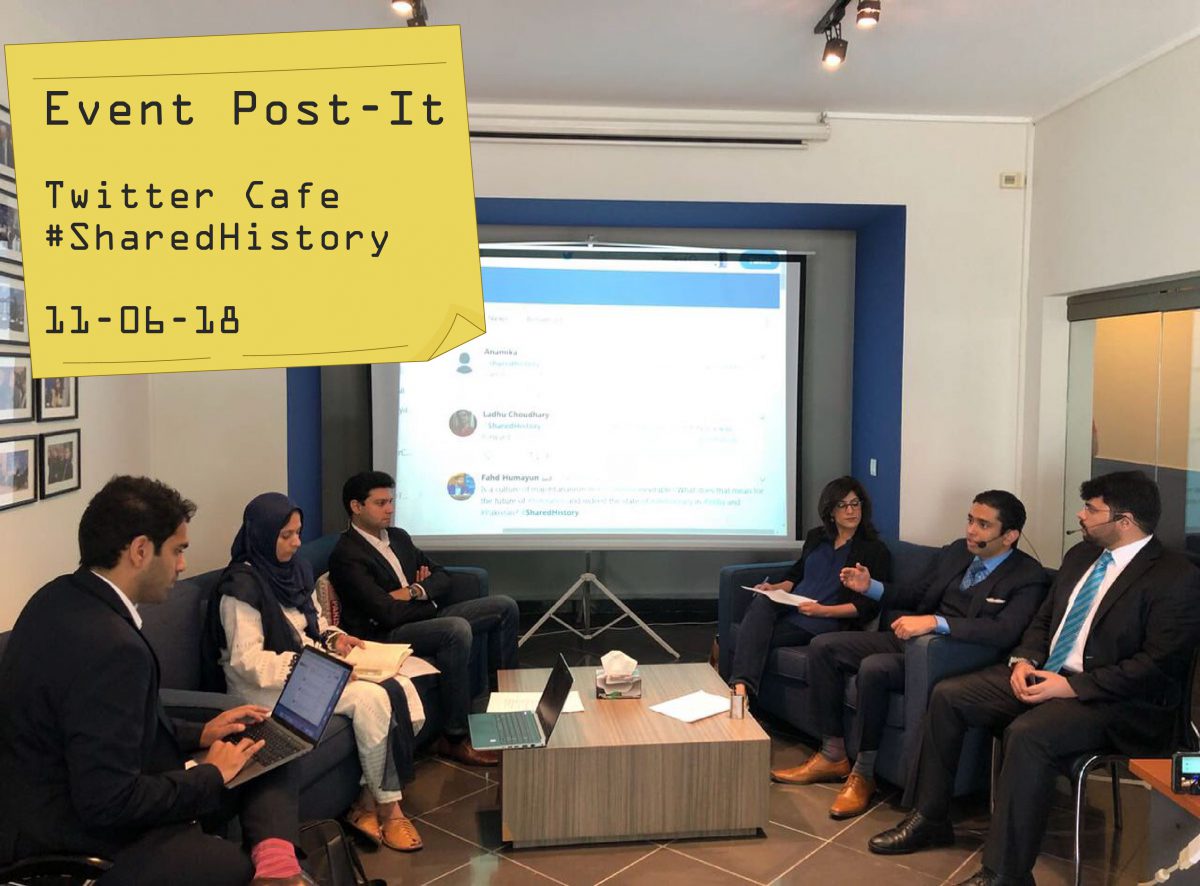

Jinnah Institute’s Twitter Café on #Shared History

Date: June 11, 2018

On 11/6/18 Jinnah Institute held a Twitter Café in Islamabad with the objective of connecting social media users in India and Pakistan with the hashtag #SharedHistory. The event aimed at creating a policy-focused debate on social media on the state of Indo-Pak bilateral relations and history’s role in shaping public discourse and political perceptions in South Asia. A live panel discussion at Jinnah Institute comprised of multimedia journalist Amber Rahim Shamsi, lawyer Yasser Latif Hamdani, social activist and commentator Ibrahim Qazi, television anchor Taimur Shamil, and Quaid-e-Azam University Professor Sadia Tasleem who helped moderate and steer an online discussion on the implications of shared historical legacy and conflict in South Asia.

Speaking on the occasion, Amber Rahim Shamsi felt the India-Pakistan relationship would continue to simmer until new governments were installed in both capitals. “I don’t know if the relationship can move forward just yet, but we can and must contain crises from flaring up,” she noted, adding that the confidence to trade and promote cultural exchanges could help mitigate fear of the other. She further held that while social media tended to be reductionist, it was also the most abundantly available forum out there enabling young Indians and Pakistanis to air their frustrations but also engage with each other in an unregulated space. She ended by observing that censorship was a challenge for both countries, and that a concerted effort was needed to protect freedom of expression in light of state-sponsored curbs on fundamental rights.

Yasser Latif Hamdani was of the view that nationalist expression did more harm than good, culminating in a move towards majoritarianism in the subcontinent. He suggested that both nationalism and majoritarianism were byproducts of toxic narratives used to crowd out pluralist expression. Instead he advocated for constitutional states in South Asia with sufficient checks and balances so as to prevent majoritarian tendencies from taking over. He further held it would be useful for historians to write a collective, common history for South Asia, and one that could be used to advance peace and security, and debunk false narratives. In this regard he acknowledged recent work by Professors Ali Usman Qasmi and Pallavi Raghavan to co-teach a course on South Asian History using virtual classroom technology. Sadia Tasleem added that it was important to develop a sense of shared empathy through textbooks and classroom conversations, and that teachers in India and Pakistan had a responsibility to foster greater critical engagement with the past, and with the present. She also maintained that events that transpired on the Line of Control (LoC) or in Kashmir only re-enforced a sense of imagined conflict, and perpetuated the anger and populism that fuelled hostile narratives on either side of the border.

Ibrahim Qazi said that it was not possible to delete or rewrite history, and that the scar tissue from major conflict including 1971 and 1999 continued to have a lasting impact in shaping public narratives. However geographic proximity and shared challenges meant that both India and Pakistan would eventually have to talk to each other. Taimur Shamil acknowledged the role of people-to-people contact in recently helping reduce some of the existing bilateral trust deficit, and noted that recent initiatives by Pakistan such as allowing Indian journalists to visit Waziristan, and inviting the Indian defense attaché to attend the Pakistan Day parade demonstrated diplomatic maturity. “Let’s not leave the conversation to politicians. Academics, journalists, civil-society have agency and should make sure they meet and interact despite existing barriers,” he observed.

Participating online, historian and LUMS Professor Ali Usman Qasmi was of the view that the experience of Partition had shaped the worldview of successive generations of Pakistanis hailing from refugee families: “For Pakistan, 1947 is about an act of sacrifice for the establishment of a new state, in India it’s about a sense of loss, both appropriate it for ideological purpose” he tweeted.