Policy Brief

India, Pakistan and the Pandemic: Community of Shared Future?

by: Haroon Sharif

Date: March 31, 2020

India, Pakistan and the Pandemic: Community of Shared Future?

Abstract

Crises are often the crucible for old challenges to be addressed in new ways. The COVID-19 pandemic may just force the region to re-think its political, strategic and development priorities in order to address the fragility of its structural weaknesses as well as the straitjacket of geo-politics it has been stuck in for several lost decades of regional disconnect. Prolonged conflict between India and Pakistan has been a binding constraint to South Asia’s growth potential in catching up with the development levels of China and South East Asia. At the same time, profound changes are becoming visible with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to connect key regional economies with an objective of developing a “community of shared future”. All evidence suggests that regional economic stakes in South Asia are rising, particularly from China, East Asia and the Middle East. Could this be a driver of change for growth, peace and stability in South Asia? Given that the potentially devastating impact of COVID-19 pandemic could open up space for dialogue, and influence old ways of working and thinking in South Asia, it is critical to have a fresh look at the way bilateral diplomatic relations could be restructured by mapping the possibilities of a post-crisis regional dynamic. The underlying conditions are very much in play. A rising graph of regional private investment, coupled with large youth cohorts and the unstoppable rise of digital technology could combine to challenge a major change in the status-quo in South Asia.

South Asia is lagging behind

The political context of Pakistan and India’s bilateral tensions has turned many dreams into mirages. With continued and increased economic and political volatility, the South Asian hope to catch up with growth and development levels of ASEAN[i] countries now seems a far-fetched ambition. Prolonged regional conflicts and internal fragmentation have resulted in more than a lost decade of potential connectivity, regional trade, investments, reforms, innovation and improved competitiveness. Tensions between India and Pakistan have kept serious investors away from the region due to a perceived higher operational risk. The already tense situation worsened during the past few years where internal political populism trumped the rational economic choices of growth and shared prosperity for over one billion people.

Just a few years ago, South Asia was projected to be among the fastest growing regions in the world with an average GDP growth projection of almost 7%. According to the World Bank’s half yearly economic assessment of November 2019, apart from Bangladesh and Nepal, growth in South Asia has significantly slowed down, casting uncertainty on the possibilities of a potential rebound. The growth projections in both India and Pakistan have declined by half from the estimates of 2018. The strong demand which was driving high growth in South Asia has slowed down by 15-20 percent in India, Pakistan and Sri-Lanka. The industrial growth and imports have plummeted, revealing a sharp economic slowdown in coming years. The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to further slowdown global growth and tough choices will have to be made to get back on the desired growth trajectory.

Given its sheer size, the Indian situation provides for the most cause for concern. Growth rates have fallen from a peak of 9.3 percent in 2016 to 4.5 percent in the last quarter of 2019 – the slowest growth in years. Despite a slashing down in interest rates by the Central Bank, the investment climate remains uncertain. With growing social tensions linked to the country’s recent Citizenship Amendment Act which has recently generated international headlines, India’s economic rebound in 2020 remains questionable.

In the case of Pakistan, the government will have to deal with the painful costs of a prolonged low growth period which may lead to further internal tensions and lack of attention towards rapidly changing regional dynamics. Pakistan has failed to put in place structural reforms to deal with its chronic twin deficits which compel the country to opt for periodic macro-economic stabilization bailouts from the IMF. The current growth projection of 2.8% is far below the required level needed to create jobs for a young labour force entering the job market every year.

Historically, the political leadership of both countries has attempted to deal with internal weaknesses by distracting people’s attention towards territorial disputes and by heightening tensions on the borders. Such populist hype has helped politicians win elections as well as strengthen the rationale for higher defense spending. The fundamental question for both India and Pakistan is not a new one. It is about their willingness to consider a change in this regressive security led mindset to a responsible engagement that could promise hope and prosperity to over a billion people in the upcoming Asian century. At this juncture when Asia is bound to rise as a global economic center of gravity, unconventional and innovative approaches should be on the table instead of policies and ideas that push for the same kind of unproductivity in the composite dialogues between two nuclear armed neighbors.

Can Covid-19 change public policy and diplomatic mindsets?

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked urgent questions about the impact of the disease and the associated public public policy responses on the real economy, politics, security and the overall social contract. The global challenge of dealing with the painful outcomes of this crisis seems to be forcing people to fundamentally alter their thinking patterns, ways of working and approaches towards dispute resolution. In her recent statement, the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned that “it is clear that the global economy has now entered a recession that could be as bad or worse than the 2009 downturn”.[ii] Each country is struggling to deal with the huge economic and human cost of this unprecedented tragedy. The potential impact of this global outbreak is expected to be particularly severe on fragile states and conflict zones. Therefore, the United Nations Secretary General has appealed to the warring nations for an immediate ceasefire across the world to focus on humanitarian efforts and to open precious windows of diplomacy[iii]. It is clear that response to this disease is likely to negatively impact the supply of humanitarian aid and will cause disruptions in peace efforts. In South Asia and the Middle East, Syria, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India will have to deal with these dynamics.

On a positive note, there have been signals from a few governments to ease tensions in these testing times. For example, President Trump has called President Xi Jinping to discuss shared strategies against COVID-19, United Arab Emirates and Kuwait have offered humanitarian assistance to Iran and Pakistan’s Prime Minister has called for easing sanctions on Iran. In case of South Asia, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi convened a video conference of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) states to discuss a collective response to the shared threat of COVID-19. India also pledged $10 million Emergency Fund for SAARC Countries. Some see this as India’s response to the increasing geo-political influence of China, but this gesture has been generally welcomed by the SAARC countries. Pakistan’s Foreign Office has indicated its willingness to engage with India on this situation. Pakistan has also demanded the removal of curfew in Jammu and Kashmir to ease logistic barriers for timely delivery of health service in the valley. If rational decision-making returns to the region, there is plenty of room for both countries to share knowledge about emergency health services delivery and cash transfer programs for the poor.

The negative economic impact of COVID-19 has already triggered restlessness among people in both countries, and both India and Pakistan have announced financial packages for the lower income quintiles and priority business sectors. According to Bloomberg, the global economy is expected to decline by one to three percent as a result of the overall slowdown of movement and economic activity. Tourism, aviation, construction, financial services and manufacturing will be the worst hit sectors from this situation. A recent paper from the leading researchers associated with the US Federal Reserve Bank examined the impact of the 1918 Flu pandemic and resulting interventions on real economic activity. The authors delivered two key messages i.e. the pandemic leads to a sharp and persistent fall in real economic activity with negative effects on manufacturing activity, the stock of durable goods, and bank assets, which suggests that the pandemic depresses economic activity through both supply and demand-side effects.

India and Pakistan cannot isolate themselves from such global economic shocks and are likely to be hit hard in terms of foreign direct investment and significant reduction in trade volumes. Pakistan has recently witnessed outflow of over $1.0 billion which were invested in government securities by international funds. With compressed global demand and supply, manufacturing and export sectors in both countries will get a hit. This situation will force the political leadership of both countries to focus on safeguarding and rebuilding local economies in the next two years. It could also lead to a window of opportunity for both India and Pakistan to open up trade to tap the potential of a large South Asian market to tackle the pressures of global demand compression. For this to happen, the pressures will have to come from the private sector as the political leadership in both countries would need a strong voice demanding this breakthrough.

The spread of COVID-19 is a rude reminder to all the countries which have criminally ignored social sector investments, particularly in the health and education sectors, and have disproportionately directed fiscal resources towards unproductive infrastructure, defense and crony capitalism. Pakistan’s ranking on the UNDP’s Human Development Index (HDI) 2019 stood at 152nd position out of the total 189 countries. As it stands, Pakistan’s ranking is 13 percent below the average HDI of South Asia including Bangladesh and India. India is ranked 129 as compared to China which stands at 85. No wonder that Japan, with its highest HDI ranking in Asia, has handled COVID-19 much better than other affected countries. It is an important reminder to the people of India and Pakistan that both countries spend 1.4 and 0.91 percent of GDP respectively on the health sector which is way below the required average of 4% of GDP. It is high time to think about national security fragility with less than $70 per capita spent on healthcare in India and Pakistan. It will be prudent to start thinking about reprioritization of public policies in South Asia to deal with vulnerabilities of human security. The key question is how to influence thinking in historically rigid public policy structures protected by the old school, political populism and elite capture.

Emergence of a “new economic geography”

Stepping back from the crisis, change was already apace. That will not reverse. While global markets had been witnessing a trend of consolidation in the wake of globalization, several regional markets had started to promote connectivity to use proximity as a comparative advantage. The contours of a new economic and political geography within South and West Asia are clearly emerging on the map with enhanced connectivity among China, Pakistan, Russia, and Central Asia. This transition is already having a remarkable influence on the thinking patterns, politics, cultures and economic developments in this region. While the traditional South Asian political elite remains in perpetual denial, captured by populist internal dynamics, the sub-continent seems to have been strategically disintegrated once again. For the two South Asian nuclear powers, it is perhaps the right time to get out of their historical baggage mindsets and start working on dealing with the new realities and models of engagement with multiple players in the next many years to come. There are fundamental foreign, economic, security and overall public policy shifts which are bound to emerge as a result of the new regional alliances.

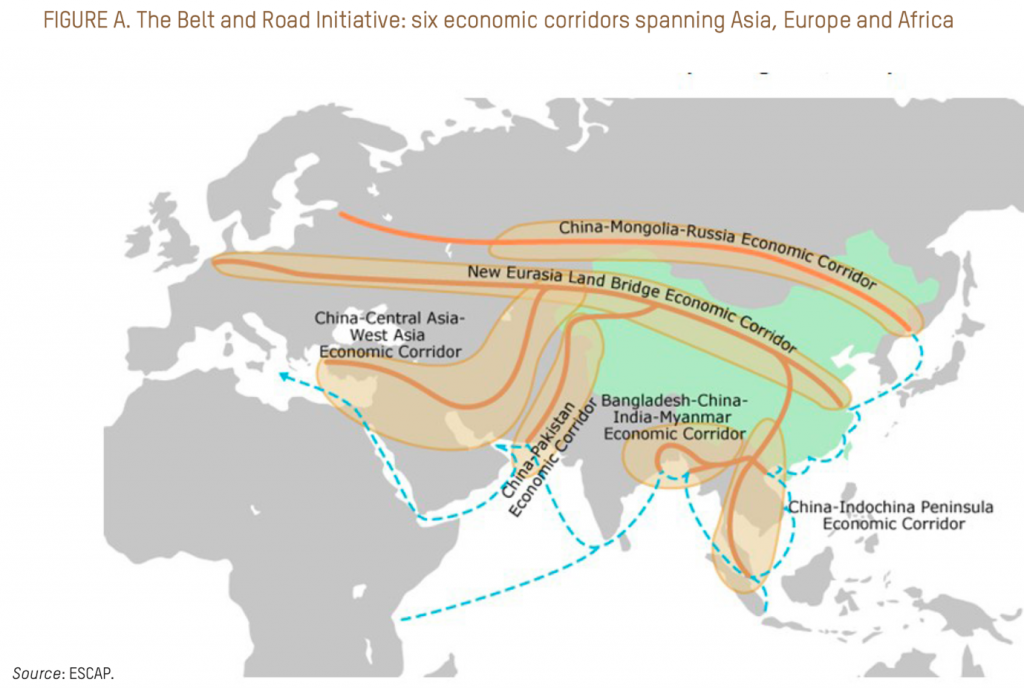

For the first time, this new geography is primarily driven by the dynamics of economic proximity rather than by the exigencies of a security-led paradigm which dominated the region for many decades. China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the strategic China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) have laid solid foundations. The success of CPEC as a transformational investment is critical for both China and Pakistan to demonstrate their ability to steer this region towards a shared prosperity. Pakistan is struggling to design and implement structural reforms to increase its institutional capacity for maximizing the CPEC impact. CPEC should not be seen as merely an infrastructure investment, it must reflect President Xi’s vision of tackling corruption, cleaner environment and uplifting the quality of life for the marginalized.

For Pakistan, three areas of structural reforms need urgent attention for managing this extraordinary transition. Firstly, Pakistan will have to strengthen the structure and orientation of its foreign service and economic ministries. The existing system has little understanding of the already changed and continuously evolving global economic landscape. Several countries have taken progressive steps by merging trade and foreign policy objectives. Pakistan needs to act on the same lines and develop a consensus on medium term strategic economic growth goals to be owned and delivered by the highest office. Secondly, there is a need to mainstream the role of private sector in the new economic growth strategy where proximity will have a central role. The country should be willing to let go the sectors which have flourished on patronage and state protection. Pakistan’s competiveness has nosedived over the past couple of decades when compared with its peer countries. Thirdly, investment in regional knowledge networks will be crucial to sustain Pakistan’s key position in the new regional markets. Pakistan must benefit from China’s phenomenal research and development expertise in all spheres and link up its universities and think tanks with south and west Asian neigbours.

Impact of Belt and Road Initiative and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

CPEC has created huge interest as well as skepticism among traditional western and Asian players in the South Asian landscape. In the eyes of Washington, India and perhaps Tokyo, CPEC is a strategic move from China to gain access to the Indian Ocean to encircle India through the deep-sea port of Gwadar in the southern province of Balochistan. Though, according to Andrew Small of the German Marshall Fund, improving transport links through the mountainous neck of land that joins Pakistan to Xinjian province in Western China is one of the lesser priority in CPEC. China is certainly interested in Gwadar as a strategic naval port in Indian ocean, but they would have done that in any case. Most of CPEC investments are aimed at improving Pakistan’s economy and opening up a large neighboring market for China[iv]. A more dynamic Pakistan would certainly help China for counterbalancing the deepening relationship between India and the USA. The militancy links between Xinjiang and extremist forces also worries China.

It is pertinent to note that China’s BRI project does not single out any significant economy in South Asia including India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. It is a matter of few years when China will become the largest economy in the world and geo-politics will circle around new economic infrastructure backed by strong financial systems. Most Asian countries have started thinking on these lines and wealthy oil rich Middle Eastern states have started planning regional diversification. It is interesting to study the increasing economic stakes of Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Qatar in both India and Pakistan.

It is crucial for South Asia to understand the Chinese growth story. After a sustained double-digit growth till 2007, China’s growth rate has slowed down to around seven percent—down more than four percentage points from the pre-crisis period. According to David Dollar, “this pattern of growth manifests three problems. First, technological advance, as measured by Total Factor Productivity (TFP) growth, has slowed down. Second, and closely related, the marginal product of capital is dropping (it takes more and more investment to produce less and less growth). The third manifestation of China’s growth pattern is that consumption is very low, especially household consumption, which is at only one-third of GDP”.

The Belt and Road Initiative: six economic corridors spanning Asia, Europe and Africa

China’s response to this changing growth dynamic is partly external and partly internal. On the external side, China launched capital intensive new initiatives like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the BRICS Bank, and the Belt and Road Initiative to strengthen infrastructure connectivity through five corridors reaching out to the western, south Asian and Southeast Asian markets. These initiatives are largely welcomed by China’s Asian neighbors; however, it is critical for BRI to look at mutual benefits rather than focusing on absorbing China’s excess capacity and low consumption demand.

India, Pakistan and China economic ties

Unfortunately, India and Pakistan have missed the boat on leveraging their phenomenal economic potential of an ideal proximity and a combined market of over one billion people. According to some informed economic modelling and estimates, the two markets could have realized USD20 billion volume of trade and investment. Both countries have themselves to blame as the pace of change does not wait for the players who fail to demonstrate their ability to resolve conflicts and continue to defy adherence to values of a responsible neighborhood. Having consistently failed to engage constructively, both countries will perhaps have to settle with two separate economic groupings in the emerging Asian century. While India has already started investing in Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, Pakistan will now be looking to integrate more with the markets of Iran, Western China and Central Asia through Afghanistan in the coming years. This new economic geography will not only test overall foreign relations but will perhaps also set parameters for a new model of responsible engagement between India and Pakistan in the long term.

Despite political changes in Pakistan, the country’s resolve to strengthen economic and strategic ties with China remain on track. The economic partnership now focuses more on industrial cooperation and development of the agriculture sector. Pakistan and China also fast-tracked changes in the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) where over three hundred new items were included in the preferential tariff structure for Pakistan. It is interesting to note that trade was not initially put as a priority under CPEC and strategies are now being discussed to increase the trade balance between China and Pakistan. Pakistan and China trade balance has shrunk to USD 10.4 billion in 2018-19 as compared to USD 14 billion in the previous year. The overall trade stood at USD 14.6bn between the two friendly neighbors. China has also provided a level playing field for import of rice from Pakistan on the same terms as offered to ASEAN countries. China also remained the largest foreign investor in Pakistan with USD 500mn investment in the first six months of this financial year. Pakistan desperately needs to increase its investment levels from a meagre USD 2-3 billion a year which is less that 15% of GDP. The Chinese economic stakes in Pakistan are likely to increase in the coming years after the connectivity between Gwadar to Kashgar becomes logistically more functional. Right now, it is subject to both institutional and post-Corona crisis delays.

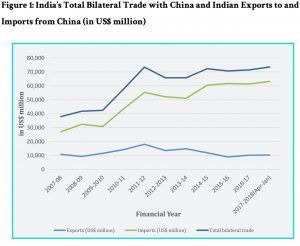

Let’s take a look at the India and China economic partnership. Bilateral trade between the two countries took a massive jump after 2011 and as of 2019 figures it grew from USD38 billion to USD87 billion.

India’s Total Bilateral Trade with China and Indian Exports to and Imports from China (in US$ million)

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India

It should be pointed out that the volume of trade did not get a hit despite serious tensions around the Doklam standoff, or China’s refusal to support India’s bid to include Jaish-e-Muhammad’s Masood Azhar in United Nation’s global terrorists list and lack of support on India’s bid to be part of the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG). Both countries have remained consistently engaged on both strategic and economic issues. Dialogue has also started on improving the balance of trade through initiating FTA negotiations. The Strategic Economic dialogue has focused principally on cooperation in science, technology and IT sectors. China’s foreign direct investment in India remained less that USD 2.0 billion till 2018 but now tech companies are aiming to set up mobile phone manufacturing as well as USD 5.0 billion investment in innovative start-ups.

With a potential slowdown in traditional western markets, and especially after the COVID-19 crisis which should act as a spur on the broader region to re-think its cooperation imperatives, both countries may find it attractive to expand economic cooperation to gain from the large size of their markets, a growing middle class and focus on domestic consumption. Indian pharmaceutical firms which control almost 20 percent of the global market share are keen to get market access in China. Overall, a stronger India-China economic relationship can be beneficial for both countries, especially considering that India plans to strengthen its industrial sector and China plans to move up the value chain with respect to its manufacturing sector. In this respect, there is little argument to be made. Investment by China in Indian firms provides them with much-needed capital to scale up their capabilities while China gains greater technological skills, especially considering India’s comparative advantage in sectors such as IT as well as other legal, consulting, and marketing services.

After COVID-19, regional economic interests may shift

Once, the COVID-19 numbers start levelling out, which may take longer in South Asia than other countries with better health-care systems, increased regional economic stakes in a time of global transition could challenge the traditional thinking about bilateral ties in South Asia. More and more Middle East based sovereign wealth funds have already been diverting their investments towards China and neighboring emerging markets. According to a global sovereign asset management study by Invesco in 2019, 88% of Middle Eastern Funds have exposure in China and are diversifying portfolios from Europe to Asian emerging markets. The study showed that 75% of sovereigns in Middle East showed keen interest in Asian markets as compared to the 47% that had shown interest in 2018. Most of these investors are increasing their stakes in technology and innovation sectors for higher returns and knowledge partnerships for sustainable economic growth in the Middle East.

Although the plummeting price of oil will impact oil-rich economies, most such governments have started working on strategies to expand their footprint in the region and to move towards more knowledge-based economies in future. The Saudi economy is still the largest in the Middle East and plans to strengthen economic ties with Islamic and other regional countries. It still has resilience and depth. The Vison 2030 document of Saudi Arabia states that the country will seek to establish new business partnerships and facilitate smoother flow of goods, people and capital. In addition, they will also strengthen regional connectivity through enhanced logistic services and new cross-border infrastructure projects. Following this, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s flagship company Aramco has big plans to set up a large oil refinery and petrochemical complex in partnership with Reliance Group in India. Similarly, Aramco has given a firm indication to set up an oil refinery in the southern part of Pakistan. This expansion is part of Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030 document where the Kingdom plans huge investments in South Asia and China. Qatar Investment Authority has allocated a significant portion of their USD 350 billion sovereign wealth fund for emerging markets of Asia, which include Turkey, India and Pakistan.

At the same time, a new financial architecture is also expanding financial choices for South Asia. The formation of Asian Infrastructure Bank ($100 bn), BRICS Bank, New Silk Road Fund ($40bn) and Export-Import Bank of China are major development financing and expertise pools that will start challenging the traditional Bretton woods institutions in future. In case of South Asian connectivity, the traditional international and regional financial institutions like the World Bank and Asian Development Bank did not play a constructive role due to their political biases and weaknesses in bureaucratic structures. The China-led financial institutions have started influencing the patterns of infrastructure development and trade financing. Large countries like Pakistan and India should diversify and expand their financing sources through these new institutions in future.

Chinese thinking of a “community of shared future”

The Belt and Road Initiative announced by President Xi Jinping in 2014 is perhaps the most significant and disruptive development aimed at changing the focus of bilateral and regional diplomacy towards economic development and shared prosperity. The objective is to promote a “community of shared future.” President Xi, in his keynote speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2020, noted that “as long as we keep to the goal of building a community of shared future and work together to fulfill our responsibilities and overcome difficulties, we will be able to create a better world and enabling better lives for our peoples. This thinking starts a new era of globalization where Chinese leadership is propagating a culture of regional connectivity while respecting the sovereignty of all countries, economic partnerships, cleaner environment and contribution towards global peace.

Time and again, China has reiterated its commitment to multilateralism and the international framework centered on the United Nations (UN) and its institutions, the World Trade Organization and World Bank. This order was created after the World War II with an objective to reconstruct and safeguard the world of nation states, and to support global governance built on multilateralism. The Western developed countries have played a major role in designing and building this order. China agrees with, and is fully committed to, economic globalization and has complied with the rules that have been governing world trade and the financial functions. This policy has required painful adjustments for China to adapt to the trend of economic globalization, but it has pushed forward and thus has been rewarded with the benefits of faster integration into the world economy. However, there is a growing feeling in China and several developing countries that the Western world has not really adhered to the real objectives of the UN framework and have started using it for the security and economic objectives of the Western club. Although China is unlikely to challenge this world order, the leadership in China will exert pressure to make this framework more inclusive and equitable.

It is critical for South Asia to learn from the Chinese concept of a “community of shared future”. China has demonstrated their economic success by strengthening trade ties with countries like India and Taiwan by de-linking economic cooperation with territorial and political conflicts. The third phase of CPEC will be focused on strengthening connectivity with both the eastern and western side of Pakistan. China has been consistent in signaling that the success of BRI depends on regional stability and de-escalation of conflict. Given the recent peace accord between the U.S and Taliban, as well as growing questions on who will fund Afghanistan after the US threat to withdraw funds, it will be difficult to imagine that the new Afghan government will not look towards China for economic development support and connectivity. With its diplomatic focus on peace and security through economic partnerships, China will remain a major influence on the regional economic development and geo-politics in the foreseeable future.

During the past ten years, Chinese investment in Europe has increased by four times. A large proportion of Chinese direct investment, both state and private, is concentrated in the major economies, such as the UK, France and Germany combined, according to the Rhodium Group and Mercator Institute. The highest Chinese investment is in the UK where China has committed more than $40 billion. In March 2019, Italy was the first major European economy to sign up to China’s Belt and Road Initiative which involves huge infrastructure building to increase trade between China and markets in Asia and Europe. It will be instructive to watch the role of these new economic partnerships on peace and stability in South and West Asia.

Potential drivers of change in South Asia

A responsible public policy and diplomatic response to COVID-19 pandemic from India and Pakistan will be welcomed by the people of South Asia and the world at large, not counting die-hard and myopic ultra-nationalists. With expected pressures on fiscal space due to both demand and supply side compression, loss of lives and livelihood, it is time for thought leaders in South Asia to reshape the discourse of dialogue towards adjusting public policy priorities towards human security and reduction of conflict. Such a response will only be possible if consistent evidence-based messages go out from think tanks, international financial institutions, media and more importantly, private sector leaders.

While India and Pakistan have failed to realize the potential gains of economic connectivity, rising economic stakes from China and the Middle East may pose a challenge to the old school that has thrived on geo-security led policies in South Asia. Both the nuclear neighbors are consistently increasing their economic ties with China and other Asian markets for enhanced trade and investment. The dividends of regional connectivity financed through BRI will also become a reality in another ten years or so. It is critical to have a fresh look at the rapidly changing and rather disruptive dynamics of regional landscape which may open up space for new drivers of change for sustained economic growth, peace and security in this region. It will become increasingly difficult for South Asians to isolate themselves from leading Asian economies in the years to come. Let’s not forget that the economic future of this region will be dominated by young entrepreneurs, disruptive digital technologies and interdependence on a strong regional market.

The first and foremost challenge for China, Pakistan and India is to jointly invest in knowledge generation for better understanding the shared value proposition of connectivity and reforms needed to attract higher levels of investment in the region. Current government structures and private institutions are not geared towards imagining and dealing with a changing South Asia in an increasingly multi-polar world. India’s quest for becoming one of the biggest economies in the world depends on the way it engages with neighboring markets, especially with China and Pakistan. A confrontational competition between the two largest economies in the world will damage the prospects of growth and stability in the region. Therefore, eminent thought leaders should consider creating more spaces for knowledge-sharing and dialogue among the three countries. One of best routes to greater future cooperation could be facilitation of contacts between young people through use of new communication technologies. It is expected that the young would be relatively free from the historical baggage of their elders and readier to engage in business with each other, though this should not be seen as automatic. Informal fora and IT platforms for discussion and business deal-making, led by the private sector and civil society, would be one obvious way forward.

The best way to learn the dynamics of BRI and possibilities for India, Pakistan and beyond is to start designing a few economic transactions which could attract multiple private sector investors. It will be difficult to use public sector investments for large scale transactions like oil pipelines from Central Asia. Such transactions require strong institutional coordination mechanisms among partner countries and much higher technical capacity to fast track project implementation. Given the political tensions between India and Pakistan, this may not be possible at this stage, but Pakistan should work on opening up the regional market to interested investors in Asia, Middle East and Europe.

In the medium term, institutional changes will have to be brought in to incorporate the impact of regional connectivity in domestic growth strategies. Currently, the planning processes in both India and Pakistan are inward looking and do not account for the potential of growth in a larger regional context. Similarly, the foreign ministries of both countries possess little skills of economic diplomacy and need to internalize the reality that the national interest will have to be redefined through higher levels of strategic engagement with key Asian countries. A change of mindset will not take place easily and there will be inevitable tensions between the new economic realities with the forces backing the status-quo. A sustained track-II engagement about the value proposition of regional economic connectivity will be required to raise the level of comfort among power structures in South Asia. There seems to be a need for a new and informal convening forum at the sub-regional level to create knowledge and dialogue space for fast tracking decisions towards leveraging the potential of possibly one of the largest regional markets in the world.

One of the key risks for slow pace of change in South Asia could be attributed to the trade cold war started by the US to curtail the Chinese trade balance. Although, India and the US have a long-term strategic partnership, this could be an opportunity for Pakistan and India to offer incentives for the Chinese firms to relocate and diversify their production lines. Global value chains will have to take a serious look at the risks of concentrating production in one country. Both Pakistan and India offer a competitive environment for several industrial sectors for investors looking at diversifying operations after the Covid-19 shock to the global and domestic economies. This can be made a reality with better planning, clarity of end-goals and real investments in the politics of regional growth.

References

Agraval, Ravi, and Kathryn Salam. “South Asia’s Year in 10 Charts.” Foreign Policy, 24 Dec. 2019, foreignpolicy.com/2019/12/24/south-asia-year-10-charts/

Arora, Kashyap, and Rimjhim Saxena. “India-China Economic Relations: An Assessment.” South Asian Voices, 21 Apr. 2018, southasianvoices.org/india-china-economic-relations-an-assessment/

COVID-19 and Conflict: Seven Trends to Watch, International Crisis Group, 24 Mar. 2020, https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/sb4-covid-19-and-conflict-seven-trends-watch

Dollar, David. “China’s Rise as a Regional and Global Power.” Horizons, Summer 2015, Issue No. 4. Brookings, www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/China-rise-as-regional-and-global-power.pdf

Emmott, Bill. “South Asia: peace, prosperity and regional cooperation.” Ditchley, 21 Apr. 2016, www.ditchley.com/events/past-events/2010-2019/2016/south-asia-peace-prosperity-and-regional-cooperation

Jacob, Happymon. “China, India, Pakistan and a stable regional order.” European Council on Foreign Relations, www.ecfr.eu/what_does_india_think/analysis/china_india_pakistan_and_a_stable_regional_order

Karki, Barabi, “Why did India decide to activate SAARC during COVID-19 pandemic”, The Diplomat, March 24, 2020.

Papatheologou, Vasiliki. “The Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative in South and Southeast Asia.” Journal of Social and Political Sciences, Vol.2, No. 4, 2019. Asian Institute of Research.

Pranav, Divay. “Five Facts about India-China Trade and Investment Relations — An Indian Perspective.” Invest India, 11 Oct. 2019, www.investindia.gov.in/team-india-blogs/five-facts-about-india-china-trade-and-investment-relations-indian-perspective

Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner. Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu, MIT and Federal Reserve Bank, March 26, 2020.

Sharif, Haroon. “New Economic Geography”. Dawn, March 26, 2018, www.dawn.com/news/1397602

Taneja, Nisha, et al. Emerging Trends in India-Pakistan Trade. Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, 2018. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2019.pdf

Ying, Fu. “China’s Vision for the World: A Community of Shared Future.” The Diplomat, 22 Jun. 2017, thediplomat.com/2017/06/chinas-vision-for-the-world-a-community-of-shared-future/

[i] ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

[ii] International Monetary Fund Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, March 27, 2020.

[iii] UN Secretary General’s message, March 23, 2020 on the World Meteorological Day.

[iv] Economist Intelligence Unit, September 2017

Haroon Sharif

Mr. Haroon Sharif served as the Minister of State and Chairman of Pakistan’s Board of Investment in 2018-19. He was Pakistan’s Lead Representative for Industrial Cooperation in the Joint Cooperation Committee (JCC) of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). He has been recognized among top 100 leaders in Pakistan in 2019. He is a member of several high-level task forces including Prime Minister’s Task Force on Economic Diplomacy. He is also a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the National Defence University in Pakistan and a Senior Fellow of the British Council, UK.

Mr. Sharif is a well-known global expert of economic policy, international development, economic diplomacy and financial markets. He worked as the Regional Advisor to the World Bank Group. Mr. Sharif worked for the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) for ten years as the Head of Economic Growth Group.

Mr. Haroon Sharif holds postgraduate qualifications in international business and development economics from the London School of Economic and Political Science and the University of Hawaii, USA. He has given key-note lectures in top universities and global forums, published research and articles at both local and international level, and won several prestigious fellowships and awards. He is frequently quoted in leading publications and invited to influential TV talk shows.

He can be contacted at hsharif@outlook.com