Ideas Conclave

Ideas Conclave 2019

Date: November 7, 2019

The Jinnah Institute convened its annual flagship event Ideas Conclave on August 7th-8th, 2019 in Islamabad. The two day long public forum connected policymakers, thought leaders and citizens to engage on issues pertinent to Pakistan and the region.

Thin Red Line: Pakistan’s Economic Trajectory

The conclave’s first session titled Thin Red Line: Pakistan’s Economic Trajectory featured former minster for defense Khurram Dastgir, former Chairperson Board of Investment Haroon Sharif, senior economist Akbar Zaidi, and for provincial finance minister Aisha Ghaus Pasha. The session was moderated by television anchor and journalist Mohammad Malick who asked panelists to share their view on Pakistan’s economic trajectory.

Khurram Dastgir pointed out that all successive governments had inherited an imperfect economy, and shared how the PML-N government had struggled to achieve a markedly low inflation rate at four per cent, in addition to the attaining a record economic growth rate highest in 30 years. Adding an extra 14000 megawatts of electricity to the national power grid may not be an emergency any longer, but posed a severe crisis for his government’s decision makers. He stated that high transactional political costs are often overlooked in analyses of economic performance. The heavy toll of the war against terror, including operations Zarb-e-Azb and Radd-ul-Fasaad, added to the PML-N government’s current account deficit and constrained choices and autonomy for development.

Commenting on the structure of our economy, Ayesha Ghaus Pasha noted that provinces are dependent on the federal government for the release of development funds, and this mechanism hinders autonomous growth. Hiked interest rates along with an undervalued currency at 10 per cent are threatening to damage the economy, whereas quick fix methods such as manipulating exchange rates to curtail imports have deleterious medium term impact.

Senior political economist Akbar Zaidi stated that the current government’s economic performance was the worst aspect of their governance ever the PTI assumed power. Growth seemed a distant prospect with the highest inflation rate experienced in five years, and further expected to rise. GDP was at its lowest ebb in nine years and expected to decline next year. A falling per capita income by nine per cent in the past one year, and FDI down by 50 percent in the same period presented an alarming picture.

Speaking of the structural constraints of Pakistan’s economy in a regional context, former Chairman Board of Investment, Haroon Sharif urged leadership to bring in quality expertise into key decision making in order to address Pakistan’s capacity issue that is considered its largest binding constraint. While South Asia boasts the largest economic growth in the world with India’s growth at seven per cent and Bangladesh’s at 7.1 percent, Pakistan’s growth rate is the lowest and continues to fall. Equating growth with short and medium term infrastructure projects may win governments electoral gains, but it is actually long term growth policies that have proved to be successful in other countries, he argued.

Breaking Bad: Women and Modernity

The second session titled Breaking Bad: Women and Modernity featured Oscar winning filmmaker Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy, rights activists and academics Afiya Zia and Farzana Bari, moderated by television anchor Amber Rahim Shamsi. Opening up the conversation, Shamsi asked the panelists if modernity was a choice to be made within traditional society, or whether it constituted a framework of values on its own.

Farzana Bari explained academic debates within feminist theory that allowed a broad range of feminist standpoints on modernity whose chief purpose was to oppose patriarchal norms, especially in societies built on capitalist values. She spoke about need for renewed activism that deconstructs the patriarchal state, whose military-industrial complex pushes women and vulnerable groups, as well as their collective labours to the fringes of society with little recompense or share in power or autonomy.

Speaking about some structural realities of Pakistani society, Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy talked about women who become vulnerable through exercising choice in marriage, taking up work, or disagreeing with a male guardian. These women often become the worst victims of sexual and gender based violence. There are no more than a dozen functional government run shelter homes for women, where victims receive a modicum of state protections, she argued. While issues of child abuse and sexual violence are slowly being taken up mainstream television, the media itself is also responsible for promoting clichéd tropes about women and reinforcing regressive gender norms, she stated.

Dr. Afiya Zia traced the historical role of Pakistan’s women’s rights movement and its struggle against military dictatorships. Successive governments in Pakistan, including the incumbent PTI government, most often adopt a welfare approach through women empowerment ministries. They see women and other vulnerable groups as charity recipients, rather than empowered and autonomous actors who can confront patriarchal orders in public and private spheres. She reiterated that feminist politics cannot be undertaken unless one tackles capitalism, and be conscious of extractive modes of production.

Literature and Resistance

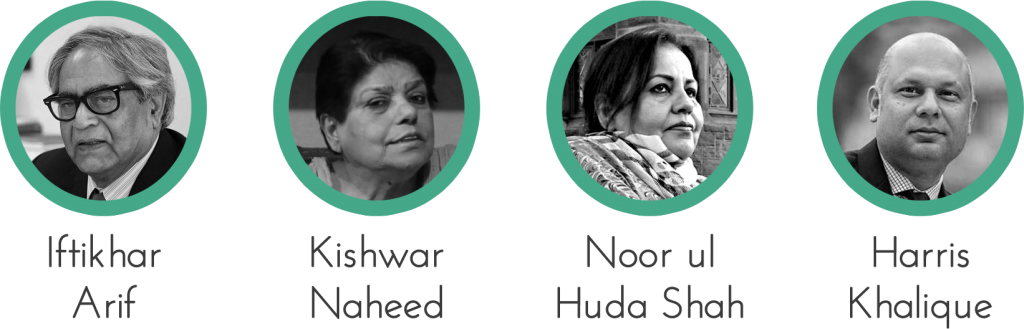

The third session of the day titled Language, Literature and Resistance featured General Secretary HRCP Harris Khalique, moderating a panel consisting of eminent poets Kishwar Naheed, Iftikhar Arif and Noor ul Huda Shah who discussed the role of literature in the political history of Pakistan, the interplay of language and identity politics, and if controls on free speech cultivate a resurgence of ideas and expressions.

Kishwar Naheed, who is best known for her powerful feminist poetry and decades’ long activism, stated that art can speak truth to power more truthfully than other political devices. Alluding to the Kashmir issue, she stated that resistance is not only part of literature but part of daily lives. Art that breaks through the binds of socio-political and cultural straitjackets is often decried as immoral or anti-traditional, but only through its wide consumption can social critique be accepted. She gave examples of television serials that were aired on PTV during military dictatorships which carried powerful messaging for social change and critiqued state policy. Kishwar Naheed underscored that popularity is never a good measure for assessing art because popular preferences keep changing. For all the popular literature, film and music produced in Pakistan, only that art has stood the test of time which effectively reflected the human condition, she said.

Iftikhar Arif highlighted the subcontinent’s monumental literary heritage, recounted movements that had a profound impact on literary forms and political ideology in India and Pakistan. The Progressive Writers’ Movement allowed writers to become effective social critics, and created space for public discourse that had never previously taken place in the public mainstream. He stated that literature influences people’s introspection of themselves and the society they are a part of. Speaking of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, he noted that the renowned Pakistani poet composed poetry about every historical and political movement in his time, deliberatey picking sides in his writing which influenced the politics of millions of readers. A strategy was devised in Pakistan as elsewhere to curtail contact between poets, academics and society, to seclude political standpoints from popular consumption and sequester alternative narratives.

Noor ul Huda Shah observed that the poetry of Bulleh Shah and Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai, who have legendary status in local folklore and poetic traditions, was not programmed on television for several years given their clear emphasis on resistance to orthodoxy and power structures. This censorship persisted because of the challenge it presented to existing narratives, and explained that the labelling of writers or poets as ‘traitors’ or ‘infidels’ has been all too common in our society, where

narratives and social attitudes are rigidly enforced. She felt that local language and history should not be separated, as distancing history from literature distorts history itself as well as the truth.

Constitution, Security and Citizenship

The final session of the first day was a key note session titled Constitution, Security and Citizenship featuring Pakistan People’s Party Chairperson Bilawal Bhutto Zardari and senior advocate and human rights activist Hina Jillani. The session was moderated by Ali Dayan Hasan.

Taking a cue from the previous session, Hina Jillani stated that literature mirrors the times we live in and provides the best clues to tumultuous political transitions. Notions of citizenship are strengthened through such transitions, incorporating complexity and diversity into citizens’ demands from the state, and the state’s endowments towards citizen welfare. However, the Pakistani construct of citizenship is based on homogeneity as a value and guiding principle, which has stamped out diversity in identity, political aspiration and participation. We forget that we are a pluralistic nation, and as individuals also contain many evolving identities, she stated. She emphasized that citizens have the right to participate at every level of governance, a right that must not be forgotten or forgone. She deemed it worrisome that the state’s was once again advancing national security at the expense of citizens’ freedoms, however, dissent and resistance are not new to Pakistan and rights movements will emerge to challenge state clamp downs on constitutional entitlements.

In his keynote address, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari emphasized that the human rights form the bedrock of democratic culture and that the provision of citizens’ rights is interlinked with national security. He argued that Pakistan’s government had transitioned from an empathetic human rights entity to one that was apathetic towards it, and is soon likely to become antipathic to the provision of fundamental freedoms enshrined in its constitution. He reiterated that citizens’ ownership of the state is essential to a true democracy, which ignored or clamped down comes with dire consequences for fragile states.

_______________

Cold War Lite: History’s Shadow on Today’s Chessboard

The second day of Ideas Conclave began with a session titled ‘Cold War Lite: History’s Shadow on Today’s Chessboard’ that focused on global strategic realignments increasingly referred to as the ‘new Cold War’, as well as Pakistan’s stakes in regional peace and infrastructure investments made possible by China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The session was moderated by columnist and development practitioner Moshrraf Zaidi, with former foreign secretaries Tehmina Janjua and Jalil Abbas Jillani, former federal minister Khurram Dastgir, and Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan Yao Jing, speaking as panelists.

Participants observed that there is a lopsided multipolarity in the contemporary global order, whereby the United States continues to be a leading power but has to contend with a rising China. Their rivalry is expected to force strategic choices on countries, but unlike the Cold War, today’s rivalry is not ideological. China is expanding its power without imposing itself too strongly on any country, and not signalling any alteration to the global financial system or military alliances. They saw that China prides itself on its indigenous model of governance, but does not wish to see a replication of it in other states. Western monopoly of technology and media networks has led to disinformation about China’s strategic intentions, they observed.

Panelists deliberated on how best Pakistan should leverage its position in light of global realignments. They noted that the West had not fully recovered from the 2008 financial crisis, whereas China had built up great economic strength and become the second largest economy in the world. The deepening China-Pakistan cooperation had been viewed with hostility in some capitals, although it forms part of a decades’ long pattern the two neighbouring countries. Pakistan was increasingly looking eastward for strategic partnerships, also reflected in its defence agreement with the Russian Federation in 2014.

Panelists reminded the audience that China remains Pakistan’s most trusted strategic partner. It is equally important that Pakistan must demonstrate its own reliance known to China. But the Pak-China strategic relationship must not prejudice other potential alliances. They felt that the United States and China are both rational players, both of whom can be leveraged to Pakistan’s benefit.

From War to Exit Wounds in Afghanistan

The day’s second session titled ‘From War to Exit Wounds in Afghanistan’ focused on the peace process in Afghanistan, the US’ impending exit, and stakes for Pakistan in regional stability. Veteran journalist and Afghanistan expert Rahimullah Yusufzai, former foreign secretary Riaz Muhammad Khan, and author and journalist Zahid Hussain spoke as panelists in the session, moderated by broadcast journalist Meher Bokhari.

The speakers unanimously agreed that the Afghan peace process was now irreversible, noting that any party pulling out of the talks at this point will have to bear a huge political backlash. The Taliban and the United States both seem eager for the talks to continue and succeed, infact the US has consistently pushed for the talks in recent years. They noted that perhaps this was inevitable, as the US never declared Taliban a terrorist group, anticipating that both parties will one day have to negotiate. However, the Taliban now have a stranglehold over the talks, as the American eagerness to exit Afghanistan has convinced them of their own veto power over the process, particularly in terms of who its participants should be. The inflexibility in their demands was reflecting this confidence. Panelists expressed confidence that once a framework for the agreement is reached, the negotiations should conclude soon after. The Taliban must take cognizance of the major socio-political transformations that have taken place in Afghanistan during the last two decades.

They saw that while Pakistan facilitated the peace talks by releasing Mullah Baradar and other Taliban leaders, it needs to recognize the limits of its own importance in the process. The Taliban are reaching out to other actors in the Persian Gulf for facilitation. Pakistan can become a spoiler by imposing its conditions on the peace, in the release or prisoners or exerting pressure on some Taliban leaders. This is a negative influence which Pakistan should refrain from exerting. But with the US-Taliban agreement within sight, it was agreed that Pakistan’s next steps must be calibrated.

Panelists expressed apprehensions about the intra-Afghan dialogue, pointing out that little progress had been made about the constitution, or the transitional government post US withdrawal. American policy on the extent of US presence in Afghanistan was also not clear; a residual presence of troops after the pullout will anger some Afghans, whereas groups like the Northern Alliance do not favour a complete American exit. Panelists agreed that the recent momentum in the peace process had generated optimism, but all parties involved must proceed cautiously, keeping in mind a more long-term vision that goes beyond the on-going peace talks. Without a regional agreement, peace in Afghanistan was a distant possibility. Pakistan, Iran, India, and China are all major regional players who need to become part of the process, and their absence can create serious deficits in regional stability, they said.

India, Pakistan and Kashmir: Where Do We Stand

A third session titled ‘India, Pakistan, and Kashmir: Where Do We Stand’ followed with academic Rabia Akhtar, former diplomat Tariq Fatemi, and former foreign secretary Riaz Khokhar as speakers, and Ali Dayan Hasan as the session moderator. The session was held in light of developments in Kashmir following the revocation of Article 370 by New Delhi, and sought to chart a course of action for Pakistan.

The panelists unanimously condemned the move by India to revoke Article 370, which gave Kashmir a special status in the Indian Constitution, terming it a de-facto illegal annexation of the disputed territory. They observed that the annexation was being lauded in most quarters in India as a historic win that the BJP had delivered against several decades of a misguided constitutional provision. Any optimism that India’s “saffron tinted judiciary” will reverse the removal of Article 370 was far-fetched.

Dialogue under the new conditions was also written off as highly unlikely in the near future. Pakistan will have to accept India’s annexation of Kashmir to have dialogue with India, panelists observed, a move that it should not undertake unless other options cease to exist. Panelists asked whether there was anything else to dialogue on, now that Kashmir had been illegally annexed? They underscored that Pakistan should refrain from any kind of military action as any disturbances in Kashmir will be attributed to Islamabad. Instead, it should target the illegality of India’s action at multilateral forums, and bring to light the gross human rights violations taking place. Panelists emphasized that all parties in Pakistan must be united on this issue, as this is not a party specific problem, but a national security and human rights issue.

Panelists agreed that India had exacerbated the Kashmir issue severalfold by this move. There will be renewed resistance from militant organizations and freedom fighters in the valley. The massive build up of troops in Kashmir by India does not allow more excuses for internal disturbance or violence, which New Delhi has always blamed Pakistan for.