Special Feature | COVID-19

Compendium | Lockdown Paradox

Date: May 13, 2020

In this feature, Jinnah Institute asked experts to comment on pressing socio-economic issues in the wake of the Covid19 outbreak and its implications, charting the possibilities for a new normal.

Killing the Virus and Saving the Economy

S. Akbar Zaidi (The author is a political economist.)

The trade-off being presented of saving lives through a lockdown to eliminate the coronavirus and killing the poor on account of the closure of economic activity is a false one. There is no denying the fact that the spread of the virus and the action taken to protect the lives of people have had severe economic consequences on all, irrespective of social class, but most affected are the working poor and others who have no savings and are dependent on daily employment. Pakistan’s majority of workers belong to the informal sector, have no job or social security, are socially and economically vulnerable, and have been hit hardest at a time of complete shutdown. While a lockdown is essential, ways can (and have been) found which allow some relief to those who have been affected most.

The immediate and most important mechanism to address the problem of a lack of immediate income in the hands of people, is to simply provide food and essentials to those who are the neediest, wherever they are located. Whether they are the urban poor or those who have not been able to earn any income on account of the cessation of economic activities, governments need to provide resources literally at their doorsteps. This requires efficient working and coordination between local and provincial governments in light of unambiguous directions and policies laid out by each provincial government.

At a stage where the poor and those in the informal sector have been hit hardest by closures, it is local and provincial governments which can play the most appropriate and immediate role. The announcement of lower interest rates or lower petroleum prices by the federal government might be of some use in the longer term and could help revive the economy, but immediate relief can only come from governments which play the main role in social sector delivery, which after the Eighteenth Amendment, are provincial governments.

Relief measures need to be coordinated with citizens’ groups and initiatives, and in order to ensure that such measures also follow government-mandated protocols, coordination needs to be made through provincial governments. The current economic crisis is one which provincial governments not only have the constitutional mandate to undertake, but the ability and capacity as well.

If anything, far greater resources and assistance from the federal government need to be channelled through provincial governments to achieve the most effective mechanism of dealing with the lockdown and its ramifications. Both the burden of health concerns as well as their cure, and the alleviation of the consequences of the economic lockdown, rest disproportionately on the shoulders of each provincial government. This is the time to strengthen them not undermine them for political point-scoring.

Hard Choices Only

Sakib Sherani (The author is a former member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, and heads a macroeconomic consultancy based in Islamabad.)

The challenge thrown up by Covid-19 to lives and livelihoods is among the most serious facing Pakistan in recent times. While the country has experienced colossal natural disasters in the past, large parts of the country and the economy remained fairly insulated from the after-effects of those events. The health as well as economic shock from Covid-19 is of a different order of magnitude, however.

In dealing with the crisis, hard choices have been imposed on government and society – none more impossible and Hobsonian than the ‘forced’ tradeoff between lives and livelihoods. This issue treads complex social choice questions that are intergenerational as well as involve income and power inequities within society. To complicate the societal and policy response, there are no ‘smart’ options given Pakistan’s institutional atrophy and weakened state capacity that preclude the fundamental building blocks of any ‘smart’ response: surveillance, mass screening and testing, contact-tracing, ability to enforce quarantines, etc.

While in the short run, the trade-off between lives and livelihoods appears to hold, in the longer run it is a false choice. A key consideration in determining any early easing of the virus-suppression strategy (with lockdowns being one element) is the impact on wider economic activity if the critical-care component of the country’s health system is overwhelmed due to morbidity associated with an unmitigated rise in confirmed Covid-19 cases. Will the economy be able to function ‘normally’ with a simultaneous raging, protracted national health emergency?

A principal lesson from the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918-19 is that US cities that undertook aggressive, up-front suppression measures saw an earlier and stronger rebound in their economies, compared to those that did not. The economy will unfortunately follow the path of public health – it cannot operate in parallel or in isolation.

What are the options to deal with the economic fallout? Given the nature of the crisis, fiscal ‘stimulus’ measures are misplaced in the short run. The immediate near-existential challenge on the economic front is not about creating new jobs but retaining existing jobs and businesses. With the economy expected to contract around 1.5-2 per cent in FY21, the loss of output from the pre-crisis baseline is approximately 5 per cent of GDP. In exceptional circumstances as these, the government should step in and cover this loss of output to a substantial extent. That means the size of the government emergency package should be at least 2.5-3.0 per cent of GDP – instead of the announced package half that size.

To support businesses, they should be offered long-term interest and collateral-free loans backstopped (guaranteed) by SBP to keep businesses afloat and payrolls flowing. The government should suspend collection of fixed and advance/minimum taxes for a period of 3 months at least, while waiving a portion of utility bills due from businesses as well as households. The standard GST rate should be lowered, and there should be a greater pass through of collapsing international oil prices to domestic consumers. These measures will also partially insulate household incomes in these difficult times. The most at-risk segment of the population should have access to expanded safety nets, such as a greatly augmented Ehsaas Kifalat program.

How will the government pay for these measures? Firstly, it will have to negotiate a suspension of IMF program conditionality for one year at least. Lowering interest rates together with seeking debt relief from multilateral and bilateral creditors will save hundreds of billions of rupees in the budget. Re-appropriation of development allocations under the PSDP/ADPs, away from longer gestation and low priority sector projects (such as highways, airports, new power projects, etc.) for the next 1-2 years, and a claw-back/imposition of windfall profit taxes on banks, IPPs, sugar, and the LNG terminals should also yield much needed fiscal resources.

Finally, the government should consider borrowing any short fall directly from the central bank. With a strong disinflationary environment underway, this is no time to be wedded to orthodoxy. At the same time, SBP should suspend its ill-conceived move to inflation-targeting at a time when the country will desperately need a growth prop going forward.

Exceptional circumstances call for exceptional policies. But exceptional policies require exceptional policymakers. This is where the current set up will need to step up.

Analytics or Values?

Haris Gazdar (The author is a Senior Researcher at Collective for Social Science Research.)

Is there a trade-off between saving lives and saving livelihoods? Individuals make decisions about this more often than they might notice. There are too many hazardous occupations to list: mining, security services, bomb disposal, firefighting, sanitation work, waste disposal, high rise construction jobs, and so many more. But also, there are multiple health hazards in occupations otherwise deemed not to be hazardous – street workers’ exposure to traffic fumes, agricultural workers’ exposure to chemicals etc. These are hard choices for the most part. We try to reduce hazard (health and safety regulations for example) but also, ultimately, leave it as a matter of individual choice. A person, supposedly, decides for herself or himself if a risk is worth taking. There are many flaws in this construction of choice, but also enough in it for most of us to sleep easy, while people put themselves at risk doing jobs that need done for our safety or comfort.

What happens when some new source of risk emerges? Such as COVID19? Our collective choice will determine whether this becomes one additional source of ill-health and death that individuals will have to face, or not. Do we accept it, as we accepted rising levels of air pollution, or traffic accidents, as a fact of life? Or do we say, as we did with respect to terrorism, that this new source of threat is not acceptable, that we will make all efforts to stop it becoming a norm? As a society we have the capacity for both fatalism and activism in good measure. Which do we choose to deploy now?

There are around 1.5 million deaths in Pakistan every year. Not all of them are what are defined as ‘premature’ deaths. COVID19 is a highly contagious disease. It has, to date, affected 10,000 people in our country of whom 230 have died. The rate of fatality has risen from 1.4 per cent to over 2 per cent in just the last two weeks. Even if just a tenth of our population gets infected, at the current rate of fatality we can expect around half a million deaths. An infection rate of a third would lead to a doubling of the total number of deaths compared to a normal year. If actual fatality rates are much lower, as some have suggested, the number of deaths might be as ‘low’ as 40,000. For context – road accidents claim around 40,000 lives while air pollution causes 135,000 deaths in a year. The total death toll in the ‘war on terror’ was estimated to be around 30,000.

For communities and countries, the analysis of a trade-off between saving lives and saving livelihoods is even more complex than it is for individuals. For individuals we can and do take shelter behind the manufactured assumption of people being free to make their own choices. But for a community or a country the choice involves saving Person A’s life over Person B’s livelihood or vice versa. Because there is no simple technical way of resolving this problem, it makes sense to pay attention to collective choices already made.

Why did we choose to draw a line under terrorism even though it was a smaller source of death than air pollution or road accidents? Was it because it arrived suddenly rather than slowly and incrementally? Was it because it threatened, if not stopped, to escalate exponentially? Was it because there was a global consensus that supported our effort? Was it because it threatened to overturn our existing order, and make us a global pariah? We made our collective choices on the basis of who we thought we were, on the basis, yes, of political considerations, but anchored in values. And once we had decided to combat terrorism how did we frame the issue of its economic impact? Did we debate the cost of eradicating terrorism, or did we belt up and created a narrative about the cost that terrorism was imposing on our economy?

Understanding the epidemiology of COVID19 is science in the making. That in itself would be reason enough to follow validated global practices to slow the disease down, so that our mental and organisational capacities gain time to catch up. We know more now than we did two weeks ago, and will undoubtedly have learned more in the coming two weeks. The same goes for any analysis of the economic impact of the disease as well as measures for its containment. What happens to our economy depends not only on the morbidity and mortality faced by our people, but also on the measures that we as well as our trading, aiding and ‘remittance’ partners take. In uncertainty of this magnitude – with possible estimates of deaths ranging from 40,000 to over a million – it is not surprising there are diverse perspectives on the trade-off between saving lives and saving livelihoods.

The questions we have to ask ourselves are the following: how low would the probability of a million additional deaths have to be for us to NOT to put almost everything we had into containing that number? This cannot be answered only through analytics. It is about who we believed we were, as individuals and as a collectivity. How we responded will then shape what we become.

Economic Dynamics and Resource Envelopes

Asad Sayeed (The author is a Senior Research Associate at the Collective for Social Science Research (CSSR), Karachi, Pakistan.)

Like many other countries, Pakistan continues to debate the trade-off between lives and livelihoods in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. Much of this debate, it appears, has had two distinguishing features in Pakistan; (i) that it is static – in the sense that it views immediate losses in comparison to immediate gains in terms of lives and livelihoods, rather than its impact over clearly defined short and medium terms; and (ii) that a muddled narrative is being put out by different stakeholders – the federal and provincial governments, other state agencies, doctors, big business and small traders. That competing interests will pull in different directions is routine but when the political leadership is unable to aggregate this diversity and put forth a coherent perspective in an emergency, it inevitably leads to confusion amongst the public at large and fragmentation at the policy level.

Part of this confusion is also reflected in determining the fiscal response to the pandemic. Granted that it is an evolving situation but some determination of size of the resource envelope that can be brought to bear for ramping up the health infrastructure, the provision of social protection and saving small businesses during the pandemic will help different tiers of government to calibrate their responses in a more focused manner. It will also reduce uncertainty in markets and the public at large. Transparency will not hurt in an emergency. It can only help.

Dynamic Thinking on the Economy

From what we know about epidemics in general and Covid-19 in particular, flattening the curve of the disease requires slowing down the economy. Bringing down the rate of spread (known as R naught in epidemiological lingo) through a lockdown at one or several points in time will impact the economy differently. Therefore, the relevant metric to assess the economic impact in this situation should not be the here and now but an annualized cycle (short-term) and the medium-term future period, say the next 2-4 years.

Historical analysis of the Spanish Flu of 1918 as well as preliminary modelling on the Covid-19 pandemic done by Yale University demonstrates that initial lockdowns reduce the spread of the disease and ease medium-term pressures on labour supply and aggregate demand through reduced rates of fatality and morbidity. By not implementing a lockdown until the R naught declines (or the curve of Covid-19 positive cases starts declining) we will be trading off livelihoods in the immediate term with more cycles of the pandemic in the future. We will thus have more cycles of shortages in labour supply – because of higher rates of death, morbidity, and caregiving for those who are sick – as well as disruptions in supply chains and aggregate demand in the short and medium future. Strict initial lockdowns can result in a V shaped recovery in terms of economic growth, whereas a more ambivalent response will mean the recovery will be U shaped and if the virus is allowed to run riot, then we are staring down an L shaped economic outcome over the next four to five years. Choices made along this spectrum now will determine economic outcomes in the short to medium term future.

It goes without saying that lockdowns hit those without a secure means of livelihood (casual and daily wage workers as well as those in small businesses) the hardest. Lockdowns will also collapse if supply chains for essentials are not kept functional. Thankfully so far, the supply chains have by and large worked relatively smoothly throughout the country. The matter of social protection, however, has left a lot to be desired. The Federal Government is in the process of disbursing Rs. 144 billion amongst 10 million plus women who have been on the BISP register through the Ehsaas Program. While there may be some overlap between those who have specifically lost livelihoods because of the lockdown, these lists are predominantly rural and the pandemic spread so far is mainly in the urban, metropolitan areas. This misspecification in targeting is being addressed now through a separate scheme, losing precious time, which in turn has impacted the legitimacy of lockdowns.

A muddled narrative on the lockdown as well as delay in rolling out appropriate social protection support has given currency to the notion of ‘smart lockdowns.’ These models are based on the observation that both the administrative capacity and legitimacy of a full lockdown is limited and the short-term cost of a full lockdown is too high in terms of livelihoods. Therefore, after widespread testing, there should be a ‘smart’ lockdown of those geographical ‘hotspots’ where there are more Covid-19 cases, while keeping other areas open. This method is premised on proactive (rather than the currently prevalent reactive) testing. This begs the question about the fiscal and administrative capacity to test proactively and to do it fast enough and its data processed swiftly so that a smart lockdown can be implemented. As a result, even after a fortnight of the mantra of smart lockdowns being peddled, it is yet to begin at any level.

The Resource Envelope

Much of the confusion regarding the policy on lockdowns is underpinned by an implicit notion that the State lack resources to provide adequate protection to the poor and simultaneously ramp up the health infrastructure. But how limited is the resource envelope? This debate has not happened yet in Pakistan. Knowledgeable commentators have put estimates in the range of 2.5 to 5% of GDP. Whether it is within this limit or can be more is essentially a function of the subjective assessment of the political leadership on their perception of the pandemic. Another way to think about the resource envelope the nation is willing to roll out is to juxtapose the situation with a war with a visible enemy.

The Covid-19 pandemic has altered the contours of Pakistan’s fiscal space on both sides of the ledger. On the one hand, fiscal space has been created because of aid from donors – the IMF, World Bank, Asian Development Bank, debt deferment from the G-20 – and from a significant reduction in international oil prices and savings on interest payments because of the decline in interest rates. On the other hand, the lockdown has reduced tax revenues (both FBR and provincial revenues). Pakistan’s exports have taken a hit because of the global nature of the pandemic and remittances from overseas Pakistanis are expected to reduce also. Whether or not both sides balance each other out is, however, just one element of fiscal space. The government has room to reallocate resources from the existing allocations, mainly from PSDP expenditures and the defence budget. The federal government also has ample room to borrow domestically and if push comes to shove, the central bank can enhance money supply, even though that will be inflationary. To put it simply, the federal government’s fiscal space has a fair degree of elasticity.

The other issue regarding the resource envelope is distribution of resources across the federal government and the federating units. Because of their constitutional mandate, the bulk of the health expenditure is being borne by the provincial governments. They are also incurring a cost in administering the lockdown and where possible providing social protection as well. They are, however, in a fiscal bind. Because of the reduction in FBR revenues, the provinces will take a hit on their share of divisible pool taxes and their ‘own source’ revenues will also decline because of the lockdown. Additionally, the borrowing capacity of provinces is close to naught.

In this situation, it is the federal government that has a two-fold responsibility. One, to determine the fiscal space that is available and second, to create mechanisms for the provinces to overcome their resource constraints. Will the federal government provide grants to provincial governments, create a special zero interest rate credit line for them through the central bank or deduct it from future shares of their divisible pool allocations? These are important questions that need discussion and resolution. Fortunately, Pakistan’s constitutional architecture allows for these matters to be resolved. The National Economic Council, the Council of Common Interests and the National Finance Commission are forums where these issues can be debated and resolved amicably. As the pandemic peaks and the annual budget season is on the anvil, these matters have to be brought on the front burner.

Expand Ehsaas, Extend Lockdown

Abid Hasan (The author is a Former Operations Adviser World Bank.)

Pakistan’s health crisis could explode, gravely crippling the economy and national security, if the lockdown is lifted prematurely. The whole world is grappling with the lives vs. livelihoods debate. Everyone agrees that in developing countries, the balance should be in favour of livelihoods. At the same time, all epidemiologists fear that non-scientific easing of lockdown is a dangerous strategy. In Pakistan’s case, the debate is driven by the misplaced views of the economic team that “we cannot have a prolonged lockdown as we are poor and can only afford a modest relief program.” A safer option for Pakistan is to expand the Ehsaas and business employment protection programs, follow a smart lockdown for at least another month or so, and as far as practicable, enforce social distancing and wearing of homemade masks in markets.

Extending the lockdown would increase the suffering of poor, and further depress economic activity. To counter that, the Ehsaas program should be significantly expanded. The aim should be to provide Rs. 10,000 per month, for 2-3 months, to at least 90% of all households – around 28 million poor and low-income households, comprising daily wagers, subsistence farmers, and workers of SMEs in retail, service and manufacturing sectors.

In addition, SBP’s loan scheme to encourage businesses for keeping employees on the payroll, must be revised. Around 90% of the 3 million or so retail, service and manufacturing businesses, do not have a loan. They will not borrow now — when the future is so uncertain — when they have never borrowed in good times. The SBP scheme should be turned into an outright unconditional grant scheme, at least for the SMEs.

The proposed program would cost perhaps an additional Rs. 1.5 trillion. Including the already announced program of about Rs. 1 trillion, the total cost would be about Rs 2.5 trillion or 5% of GDP. This level of additional deficit should not be a cause of concern and can be financed through a judicious combination of more public debt and a one-time ‘helicopter money’ financing by SBP.

Out of the box thinking can save lives and livelihoods. No doubt deficits and public debt will balloon, and maybe inflation might increase, but we can correct all the macroeconomic imbalances if we achieve victory over the virus.

Social Protection and COVID-19

Safiya Aftab (The author is Executive Director at Verso Consulting)

Introduction

As of end April 2020, Pakistan has more than 16,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19, and over 350 deaths.1 As this human tragedy unfolds, more material concerns are also being debated alongside. Along with2 much of the global economy, Pakistan too, is expected to undergo a recession – only the second in its 73-year history (the first was in 1951-52).

The implications of this for a workforce of almost 60 million are staggering. In the event that the pandemic does not abate in the near future (and this indeed is what is likely), it falls upon the State to ensure that the basic needs of at least the poorest sections of society are provided for. This paper argues that social protection and relief are the State’s key weapons in this fight against COVID-19. Rather than endangering lives by rushing to allow economic activity, the emphasis has to be on devising the means to cover the most vulnerable sections of the population.

Economic Implications of COVID-19

The World Bank estimates that growth in Pakistan in FY 2020 will contract by 1.3 per cent,3 as a result of the slowdown in economic activity in the last four months of the fiscal year.4 The outlook is not very positive for the near future either – growth is not expected to recover before FY 2022, when it is expected to reach barely 3 per cent. The agriculture sector is likely to emerge relatively unscathed (barring the vagaries that it is subject to anyway, due to fluctuations in water flows, pest attacks and unfavourable weather conditions). However, manufacturing is highly vulnerable. Only units producing essential items are in operation March 2020 onwards, and even the ones that are working are plagued by supply chain disruptions. The services sector, which typically accounts for more than half of the GDP, has been badly hit as retail and wholesale trade has crumbled, and transport, storage and communication are largely inoperational. In essence, about 80 per cent of the economy is badly affected.

The implications of this for the workforce are staggering. Economists at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) analysed data from the Labour Force Survey 2017-18, and found that up to 18 million people, or about a third of the total labour force, could lose livelihoods, particularly if the economy moves towards a complete shutdown.5 Two thirds of those rendered unemployed are likely to be daily wagers.

The federal government’s response to this scenario has been marked by confusion. It has resisted a strict lockdown, and has time and again stressed the need to allow economic activity to resume. In this, it has been thwarted by three provincial governments (Sindh, Balochistan and later Punjab) and by the medical community, which has come out through its designated professional associations to warn policymakers of the potentially disastrous consequences of a resumption of business as usual. As things stand now, a (smart?) lockdown is in place throughout the country until at least mid-May. What all it covers and the extent to which it is being enforced varies from province to province and in the federal territory.

While it is impossible to deny the potentially devastating effects of a lockdown on the economy, international experience suggests that relaxing rules on movement and interaction are likely to prolong the pandemic. What should the government then do?

COVID-19 Social Protection Measures

The first COVID-19 case was confirmed in Pakistan on February 26, 2020. Within weeks it was clear that the number was going to go up substantially, beginning with cases detected in travelers returning to the country, and progressing to local transmission.

Multi-sectoral Relief Package, March 2020

The government announced its first major relief package on March 25, when Pakistan’s total confirmed cases had just crossed 1000.6 This qualified as the single largest poverty relief package ever issued by the Pakistan Government, and included relief measures worth Rs. 1.25 trillion. Of the total, Rs. 200 billion was to be distributed to daily wage laborers (mainly as food packages). Rs. 144 billion was to be distributed as cash relief in the form of a lumpsum payment of Rs. 12,000, to vulnerable families, as identified through the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) registry. An estimated 12 million families are expected to benefit from this initiative.

The relief amount for households was calculated as Rs. 3,000 per month for four months, with Rs. 3000 estimated to be the typical expenditure on groceries for an average family in a month. It is to be kept in mind, though, that this amount is just 17 per cent of the federal government mandated minimum wage of Rs. 17,500.7 The Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) reported that 37 per cent of total household expenditure is typically on food for families in Pakistan in general.8 Applied to the minimum wage, this means that typical food expenditure for an average household comes to about Rs. 6,475. The relief package thus just about provides the means for families to avoid starvation – it cannot be considered as a means to cover even basic food requirements. Nevertheless, it appears that the choice was between increasing the number of potential beneficiaries vs. providing substantial relief to a smaller number. The number of households receiving the unconditional cash transfer from BISP is currently 4.7 million – and these are considered the most vulnerable households as per the last BISP poverty scorecard survey completed in 2010.9 The government’s decision to almost treble that number of beneficiaries for the COVID-19 relief package makes sense, given the widespread poverty impact of the pandemic.

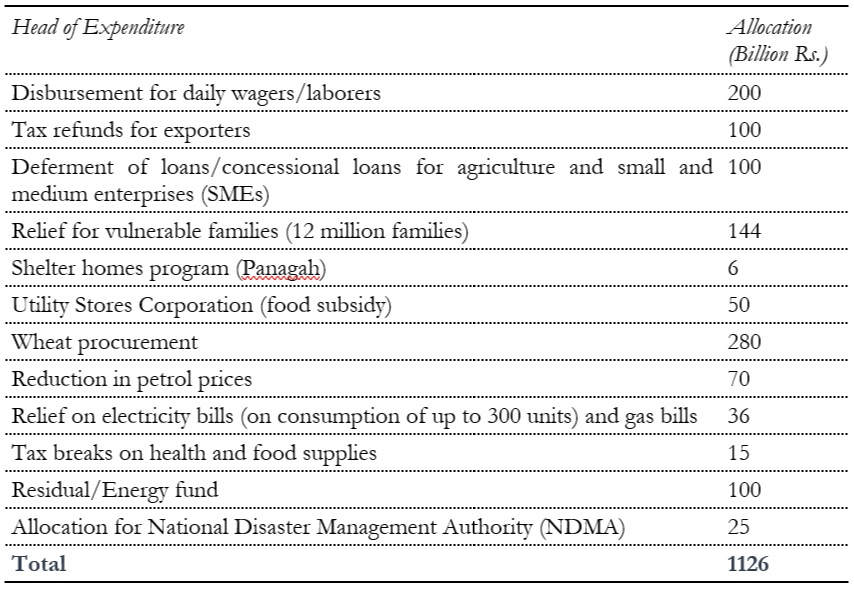

The expenditure heads proposed under the package are given in the table below.

Table 1: Breakdown of Prime Minister’s Relief Package – March 2020

Source: Press statement, Ministry of Finance.

A quick analysis of the package shows that about 40 per cent of the allocation is in the form of direct relief to the poor (allocations for daily wagers and vulnerable families, food subsidy through Utility Stores, funds for shelter homes, and relief on utility bills). About 60 per cent of the package does provide relief for vulnerable segments of society, but is also aimed at protecting losses in commodity producing sectors, and those engaged in production processes. These allocations included ones for tax refunds and tax breaks, deferment of loans, wheat procurement and the energy fund. Thus, the government appeared to be targeting two fronts even in a relief package being touted as a safety net provision for the poorest of the poor.

Package for Unemployed Labourers and Small Businesses

Another package was announced by the Prime Minister on 2nd May, which aims to provide relief to labourers and small businessmen. The Prime Minister said that the Ehsaas program, the government’s flagship social protection entity, has launched a portal to register unemployed labourers, who will then be provided cash grants of Rs. 12,000 total issued in instalments. The package also includes provisions for payment of electricity bills of small businesses for up to three months. According to an earlier statement, Rs. 75 billion has been approved for the package, which will benefit about 3.5 million small businesses. It is not clear if this package is a subset of the multi-sectoral relief package described earlier, or is a new initiative.

Ehsaas Ration Portal

A donor-beneficiary linking portal, which was made operational in end April, the Ehsaas Ration Portal requires both donors and potential beneficiaries to register with the program. Beneficiary data will be scrutinised against the Ehsaas database to ensure eligibility, while donor data will be assessed for transparency and tax compliance. The Portal will allow donors to provide cash or food rations for distribution to eligible beneficiaries. The Portal is targeting large corporate donors (annual revenues of over Rs. 2 billion) as well as NGOs (approved by the Ministry of Interior). This is a new initiative, the success of which will be monitored by the Ehsaas program over the coming months.

Possible Corona-led Budget

According to the Advisor for Finance, the budget for FY 2021 will be a “Corona-led” budget with a focus on relief and rehabilitation. While tax collections are likely to fall far short of targets, given the shrinking of the economy in the second half of the current fiscal year, the government is getting significant relief from rock bottom oil prices, and fiscal concessions granted by the IMF which has committed $1.4 billion through its rapid financing facility to combat COVID-19.10 While appreciating Pakistan’s response, the IMF observed that relief measures must be “targeted and temporary” given Pakistan’s ongoing fiscal challenges.11 This, of course, is under the assumption that the COVID-19 global crisis will abate by the second half of 2020 – something that is impossible to predict.

Social Protection as a Crisis Response

Ramping up social protection measures was perhaps the key requirement in the current scenario when the estimated 70 million plus persons in Pakistan who already fall below the poverty line are at their most vulnerable. The need for the State to provide cover is even more pronounced when one considers that those already beneath the poverty line are likely to be joined by perhaps another 20 million or so who may be rendered jobless and with no access to wage labour. We discuss some of the key features of the social protection response of the government.

Extend Protection to the Poor

The multi-sector relief package was a step in the right direction, but doesn’t go far enough. Although inflation is likely to remain low in the wake of lower oil prices, 12 it is still unrealistic to expect that a household of 6 to 7 persons (the average family size in Pakistan) can manage expenditure on food and other essentials (fuel, medicines) on Rs. 3,000 per month. The government acknowledges that the relief package is meant to avert a food emergency rather than relieve poverty. However, in a situation where income earning opportunities are fast disappearing, it is important to do more than just take the edge off hunger. This is a crisis situation, and it should be possible to marshal resources from other heads of expenditure. The government may also consider reviewing the public sector development programs at the centre and in all four provinces and allocating funds only for essential projects, or those that will contribute to relief efforts in the current crisis. There is little doubt that any comprehensive social protection program will cause the fiscal deficit to balloon. But the alternative is a citizenry that realises that its welfare was not a top priority. That is a situation to be avoided.

Relief Package to Emphasise Protection

As such, the government’s multi-sectoral relief package was a much-needed policy statement, and a boost in the arm for the poorest sections of society. Nevertheless, even the relief package that was supposed to address a poverty crisis includes many elements that benefit producers and entrepreneurs. While it can be argued that these economic agents enable job creation, and thus contribute significantly to poverty alleviation, it is also true that resuming economic activity could possibly expose large sections of the population to an unprecedented health crisis. It may be wise to adopt a phased approach wherein the immediate disbursement from the package should be on income support for the poorest, and on health facilities, thus demonstrating the State’s commitment to preserving life above all else.

Targeting Through BISP Scorecard Survey to be Supplemented

The poverty scorecard survey on which BISP disbursements are currently based was carried out in 2009-10. In Pakistan, where almost 20 per cent of the population is estimated to be vulnerable to poverty, while a further 18 per cent are clustering around the poverty line, a lot can change in ten years.13 A recent review of BISP beneficiaries was revealing as it included those who had government jobs, those who had travelled abroad more than once, and those who had paid mobile phone bills of more than Rs. 1,000 in a month, to name just some of the categories against which beneficiaries were assessed. While some of the additions in the list of beneficiaries could be traced back to fraudulent practices, it is also possible that some of the beneficiaries who were removed were simply those whose circumstances were quite different ten years ago.

Just as the status of BISP beneficiaries was evaluated using other publicly available databases – cell phone bill payment records, utility bills, records of travel and employment, etc., it is possible to identify those deserving of financial support through the same means. Thus, it may be acceptable, for example, to stipulate that all those whose utility bills show consumption of units below a certain level, consistently over a period of some months, will be eligible for financial support. The government can continue using the BISP database for one lot of disbursements, but may consider supplementing that through other such means of identification to account for possible significant changes in economic status.

Support to the Non-Government Humanitarian Sector

The government’s relations with NGOs have been dire of late, with a host of new regulations on registration and grant of no objection certificates etc. The authorities claim that scrutiny of NGOs was necessitated by the covert support being extended by some notorious organizations to extremists and terrorist groups, as well as other “anti-state” elements. While the need to regulate such instances is appreciated, the authorities have in effect succeeded in rendering NGOs in-operational and largely ineffective when it comes to providing relief to marginalised communities. NGO personnel typically cannot travel freely across the country, meet with communities, or collect data. While some charity organisations continue to flourish and are doing excellent work during this crisis, there is a need to be more inclusive. The government should consider allowing a range of development NGOs, who have been constrained in recent years, but who are skilled in community level operations, to take to the field and assist in relief. There is no greater threat to national security than a despairing, desperate citizenry that does not trust its rulers or society in general, and feels ignored.

Avoid Mixed Messaging

The federal government’s response to COVID-19 has been characterised by mixed messaging. The statements of various members of the government have run the gamut from saying that this is a mild affliction that is unlikely to affect anyone other than the elderly, to advocating debt relief for less developed countries in the wake of the disaster that the pandemic is unleashing. The government’s concern for the economy is understandable. Nevertheless, the immediate concern should be the preservation of life. It is important to reassure people that resources will be diverted such that they do not face severe deprivation, although a loss of livelihoods is inevitable. Presenting a scenario where people are being told that they will starve unless they work will only add to panic, in addition to possibly endangering them and conveying a sense that the citizens of the country are on their own in the face of perhaps the worst health crisis the country has faced.

In the same vein, the government’s mixed messaging on the ferocity (or otherwise) of the pandemic in Pakistan is also creating false expectations. In recent days, a number of prominent politicians, including the Prime Minister and the Minister for Planning, have reiterated that numbers are better than expected, and that the incidence of the disease in Pakistan is lower than envisaged. The cause for this complacency is not clear, however, given that Pakistan’s testing rates are poor if not abysmal.

All that can be said with some authority is that mortality rates, as a proportion of confirmed cases, are not as high as in most western countries. Nevertheless, until testing ramps up significantly, it is not possible to assert that Pakistan has somehow escaped the worst-case scenario.

Conclusion

The latest modelling of the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that the virus will only begin to fade out in Pakistan in July 2020. The government is discussing an ease in the (already weak) lockdown. The measures being debated are the opening of more industries, some sectors such as construction, and even opening up some routes to public transport in the run up to the Eid holidays in end May. With daily case increases now nearing a 1,000, this is a highly risky strategy. The repeated assertion is that as a poor country we cannot afford an indefinite lockdown. This view does not account for the fact that allowing people to be exposed to a potentially deadly disease is hardly going to help the economy in the longer run, not to mention exacerbating issues of poverty and marginalisation. The government has an opportunity to demonstrate concern for the welfare of its citizens. If this means taking unpopular decisions, then it must do so, and explain its line of reasoning to the people. COVID-19 has changed the world. It is unlikely that humankind will not feel the impact of this pandemic for a long time to come. Now is the time for Pakistan to chart a new course where the health and safety of its people are first and foremost.

References

1 Based on less than 200,000 tests. Per day testing so far has been about 8000 tests. The number of tests is too low to get an accurate picture of incidence of COVID 19 – it is fair to surmise that the actual number of infected persons is far higher than what official figures convey.

2 See https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/pakistan/overview. Accessed 27 April 2020.

3 The fiscal year in Pakistan runs from 1 July to 30 June. The form FY2020 refers to the fiscal year ending in June 2020. The same convention holds for other fiscal years cited in this paper.

4 PIDE. (2020). Labour Market and COVID 19. COVID Bulletin No. 13. The paper posits that the bulk of jobs lost will be those engaged in the agriculture sector, but that probably refers to rural populations engaged in off-farm employment, mainly daily wage labour.

5 Data from http://covid.gov.pk/stats/pakistan. Chart titled COVID 19 – Overview.

6 Provincial governments notify minimum wage rates separately, but these do not differ substantially from the rate mandated by the federal government.

7 Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2015-16. Table 3.7.A of section titled Write Up.

8 A new census or National Socio-Economic Registry (NSER) data collection process is currently underway, but its not clear when results will be available. As of now, BISP is relying on somewhat outdated data for household targeting.

9 Press Release: IMF Executive Board Approves a US$1.386 Billion Disbursement to Pakistan to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic. PR 20/167. April 16, 2020.

10 Ibid. Paragraph 18.

11 LNG and furnace oil prices are likely to fall as well and create relief for disposable incomes. Oil is the base price, and most other forms of energy pricing are linked to it.

12 Poverty figures from Ministry of Planning, Development and Reform. (2018). National Poverty Report 2015-16. Table 5.

13 As announced by Minister for Planning Asad Umer on April 29, 2020. See https://www.arabnews.pk/node/1666946/pakistan