Second Opinion

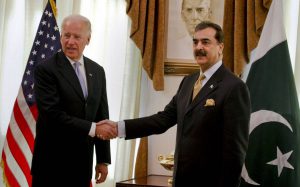

VP Joe Biden’s Visit to Pakistan

Date: January 15, 2010

Jinnah Institute seeks Pakistani policy analysts’ opinion about US Vice President Joe Biden’s visit to Pakistan and its strategic implications.

US Vice-President Joe Biden’s flying visit to Islamabad, followed by the release of the Af-Pak Review and prior to the pull-out of US forces in 2014, has generated talk in Islamabad about changes in the region’s strategic balance. It was widely noted in Pakistan that VP Biden pressed for a military operation in North Waziristan, and reiterated the argument that Washington’s patience was wearing thin.

In response, facing the extremist surge at home, the Pakistan Army continued with its policy of watchful attrition on the military offensive in North Waziristan for the moment, citing critical resource and backlash constraints. U.S. Vice President Biden’s announcement that President Obama will be visiting Pakistan this year, also drew comments about the strategic balance between India and Pakistan, primarily because this visit is positioned several months after Obama’s India tour.

In this backdrop, Jinnah Institute asked six analysts from the Pakistani strategic policy community for their opinion on the Biden visit and key policy nodes in Pakistan-US relations. Among other things, experts cautioned against high expectations and the possibility of a growing incongruence in bilateral expectations that may strain US-Pak relations in the months to come.

Military strategy will remain at status quo

In response to whether Vice President Biden’s visit would make any real changes to existing military or regional strategy in Pakistan, General (retd.) Mahmud Ali Durrani, former National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister, said no change is on the cards, as underlying issues persist. “The Americans are not too happy with the role we’re playing, and we are not happy with the support we’re getting. There is a lot of mistrust, the drone attacks continue and yet they say “˜we love you’. They are not succeeding in Afghanistan and we’re going to be made the fall guy for their failures. They’ve messed up in Afghanistan big time, they haven’t gotten rid of the poppy problem, they haven’t improved the police force, the quality of leadership in Afghanistan is worse than ours. Typically, people in Afghanistan aren’t going to blame themselves; they’re going to blame Pakistan for their failures. Pakistan is also not very happy because the US has not been able to give us the weapons of our choice. With the Coalition Support Fund, there have been problems and hitches. This is money owed to Pakistan, but there have been differences on this issue.” Mr. Durrani says that while there have may be accounting problems, the CSF remains an issue.

According to security analyst and JI Advisory Board member, Dr. Hasan Askari-Rizvi, Pakistan’s security policy is likely to remain at status quo. “It will continue to concentrate on tribal agencies where it is currently engaged in security operations. It will launch a security operation in North Waziristan at the time of its choosing, which is not going to be in the near future. Immediate action in North Waziristan is not possible for two major reasons. First, the Pakistan Army and paramilitary are engaged in at least five tribal areas where they continue to face tough resistance in spite of some noticeable gains. They will not increase their military engagement until they think that their primary security task has been completed in these tribal agencies. Second, given the resurgence of religious orthodoxy and extremism after the assassination of Salman Taseer, the army cannot afford to go into an entirely new area. These Islamic groups are a political front for the militant groups and the Taliban, they will get another cause to keep their agitation going. Any immediate action in North Waziristan will be highly destabilizing for Pakistan.”

Zahid Hussain, a journalist and author of The Scorpion’s Tail, says, “I don’t think this visit will lead to any changes in policy. This trip was part of an assessment process; Biden visited Afghanistan and then Pakistan. This trip essentially leads up to the assessment of the Afghan strategy in June 2011. It is crucial from the American point of view to review how the situation has developed; this will be central to mapping Obama’s policy in the next year.

Secondly, there is the perception that fundamentalists are on the rise after the assassination of Salman Taseer. The rise of fundamentalism was therefore part of this discussion. There was also a growing concern that Pakistan’s financial and economic stability would crumble.”

According to Hussain, with this trip, the US also wanted to assess Pakistan’s willingness to take action in NWA. The militaries of both countries have been in close coordination, so the Pakistan Army’s reluctance to open another front is not a surprise to them. Overall, it is inaccurate to call this the “Pakistan visit”: it was a wider visit, encompassing Kabul. Biden has his own view about the war; he is one of the people advocating that the US should quit Afghanistan. He was never in favor of the surge and opposes sending more troops to Afghanistan, unlike others in Obama’s government.”

Former Foreign Secretary Najmuddin Shaikh says, “I will link this to Mullen’s last statement which says that it’s important for action to be taken in North Waziristan; I think both sides talked about the importance of taking action against these elements. Whether Pakistan will agree or not, I’m not quite sure. But right now a position is developing that Pakistan cannot start placing extremists in one group or the other.”

Dr. Humayun Khan, former Foreign Secretary of Pakistan, sees no change in the strategic posture of either country. “The Americans will, however, keep pressing us to do more, particularly in NWA. Perhaps we may succumb, either to threats, or to tempting blandishments. They will continue their intensified drone attacks. This may change once the US realises that its policy, recently reinforced by the Obama review, is not working.”

Telling the US to “do more”

With the pullout of US forces from Afghanistan in 2014, the region is due to undergo a shift in political and military equations. We asked our experts what Pakistan could seek from the US in military, political, diplomatic assistance, given that it would play a significant role in the region post-2014. What leverage does Pakistan’s position allow? Finally, is there any congruence between both sides in the level and nature of expectations from each other now?

According to General (retd.) Mahmud Durrani, “The fundamental thing we need to understand is that Pakistan and USA are not of the same weight or the same size; they are completely different from each other. One is the only superpower in the world while the other is struggling for survival as a country. How much leverage can you apply? It’s only a negative lever, that “˜if you don’t do this, we won’t do this’. We don’t have a positive lever. I’m not too hopeful. “

Durrani says there are problems from both sides, “It’s a relationship with complications, with no love lost. There is a deep mistrust; we are doing things for each other because we need each other. My thinking was that this was a great opportunity to develop a relationship and we had a common treat that was terrorism. But both sides are playing games.”

According to Riaz Khokhar, the point of major divergence between Pakistan and the US is the question of India’s possible role in Afghanistan. “The US Vice President talked about good intentions towards Pakistan, but I’m afraid that this question about India’s role in Afghanistan is a very serious matter, and is going to complicate the strategic environment in the region to Pakistan’s disadvantage. If the United States says its intentions are good, then why are they promoting India’s intentions in Afghanistan? I think this is what Pakistan is talking about when it comes to the great game, it’s not about the US and the Soviet Union; they’re talking about the problem that will arise if India were to develop strategic space in the region.”

Zahid Hussain believes that there isn’t a perfect convergence of interests between the two allies, although there are some points of common interest. “Pakistan has already conveyed its concerns on what will happen in Afghanistan after the US withdrawal in 2014. Also, they must have discussed India, because that is a major concern for Pakistan in the long-term. Pakistan does not want the US to leave without a political settlement in Afghanistan. The Americans have a different perspective on how to go about it.”

“Pakistan believes that some kind of political stability in Afghanistan is crucial, and one that is not hostile to Pakistan. A serious concern is the presence of India in Afghanistan, and we have conveyed this to the Americans. However, we live under the illusion that we have some leverage, but it’s not like we can dictate terms as far as America is concerned,” adds Mr. Hussain. “It is not, however, a case that India is the “more favored” ally. Currently, there is a convergence of interests between India and the US vis a vis terrorism and the region. Between Pakistan and the US on the other hand, even if there is a common interest, national security interests do not coincide. The US has a short-term interest in Afghanistan, which is limited to capturing Osama bin Laden and to eliminating the Taliban.”

Najmuddin Sheikh argues that while Afghanistan is and should remain a legitimate concern for Pakistan, the real danger facing Pakistan is its own stability. “So, a durable, enduring and sustained relationship with Pakistan is a key US policy. We should play a role where we should do whatever we can to achieve stability in Afghanistan and then to focus on the economic strategy, transit routes, energy through Central Asia etc.”

According to Dr. Humayun Khan, “Pakistan is being short-sighted in playing the Taliban card in the hope that it will give them extra leverage with the US and a larger role in the Afghanistan end-game. Instead, it should use its influence with the various shuras to urge them to enter into an intra-Afghan dialogue with all other Afghan forces. If they are not prepared to do this, Pakistan should ditch them. In Haqqani’s case, he should be clearly told not to use Pakistan territory for insurgency activities. If he disobeys, we should proceed against him.”

On the other hand, Hasan Askari-Rizvi believes there are several things that the military will ask for in exchange for its efforts against militants. “The military needs equipment and technology to strengthen its capacity for counter-terrorism in the tribal areas. It will also require intelligence gathering and surveillance instruments to monitor the militant groups, especially their movement in the tribal area. Greater cooperation between U.S and Pakistan is needed to address the problem of the two-way movement of the Taliban and other elements across the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Pakistan also needs financial support or socio-economic development and to salvage its faltering economy. Pakistan can play a stabilizing role in the region only if it puts its economic and political house in order, which may not be achieved in the near future. Therefore, Pakistan will not have the full capacity to work effectively to stabilizing the region, as it needs to stabilize itself first.”

According to Mr. Hussain, “Pakistan’s economic predicament limits its leverage vis-a-vis the U.S. However, a regular and frank diplomatic interaction with the U.S. can convince the U.S. of what Pakistan can or cannot do. The U.S. needs Pakistan for handling Afghanistan in the present-day context as well as in the post-2014 period. The geographic location gives Pakistan a unique position, which helps Pakistan to exercise leverage in interaction with the U.S. The key issue is not leverage, but how both can invest in issues of common interest.”

Strategic Imbalance between Pakistan and India

Jinnah Institute asked the policy community how far they expected VP Biden’s visit to go in terms of shifting the strategic and diplomatic imbalance that Pakistan had noted in the region with Obama’s visit to India, or if indeed a shift was at all possible.

General (retd) Mahmud Ali Durrani believes Pakistan should review a policy of making strategic comparisons with India. He joins a growing body of civil society opinion that believes that the US will invest in building upon strategic convergences with India. “In the American perception, India can offer a lot. It’s a much bigger country than Pakistan, it can be a counterweight to China. The ground reality is that their middle class is bigger than Pakistan’s population, even though they have a sizeable population that’s poor. There are a number of factors that will remain constant in helping India and the US to grow together. They may have differences when India grows further and tries to expand its influence in the South Asia, South-East Asia, South-West Asia region, but that’s in the future.

Riaz Khokhar agrees that there would not be a real shift. “The US is betting on India and has been doing so for a long time. They want India to become a counter to China in the region and Pakistan is a small factor when it comes to that.”

“The purpose of this visit was not to “balance” diplomatic ties”, says Zahid Hussain, “Biden’s visit to Pakistan is part of a long-term strategy where we are part of a regional issue for the US. Visits such as this one do not decide strategy, nor do they have grand diplomatic outcomes such as “balancing” with India. The focus of this trip was almost entirely Afghanistan; Biden stayed in Kabul for a few days. If anything, this was a visit to Afghanistan and Pakistan, but it was certainly not a diplomatic visit to Pakistan alone.”

Najmuddin Shaikh says that while Biden’s visit had been scheduled earlier, it has to be linked with the assassination of Governor Taseer and the subsequent reaction that “has come as a shock”. “Even though there is extremism in the country, yet this sort of reaction and the number of mullahs that came out has been found disturbing. When it comes to Obama’s visit to Pakistan, he will stress, as he has done before, that there should be an Indo-Pak dialogue to resolve problems, and the US will play a passive role in this, but not an active one,” says Shaikh.

“I do not agree that Obama’s visit to India gave rise to a strategic imbalance in the region. It merely recognized realities”, says Dr. Humayun Khan, “The Americans may have supported Pakistan at times because they had a particular axe to grind, but they always saw India as the most important country in South Asia. In the long run, Pakistan too must face this reality and strive for a good relationship with India.

According to Dr. Rizvi, “India and Pakistan are important to the U.S. for different reasons. Comparatively, India remains important in terms of its globalized economy and emerging market, especially with its potential to play a stabilizing role in Asia and its possible rise as a major player at the global level. Pakistan is important because of its geographical proximity to the regions that are important for the U.S. Its role is unmatched for stabilizing Afghanistan and eliminating terrorism in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Our internal harmony and economic stability are viewed as the key to coping with religious extremism and terrorism. However, the balance of American policy will be tilted towards India. Pakistan does not expect a strictly balanced U.S. approach towards India and Pakistan. It wants the U.S. to exercise its clout with India to re-open the dialogue with Pakistan on all contentious issues with the objective of resolving the problems.” Dr. Rizvi feels that this is unlikely, given the U.S’ growing economic interests in India.

“If Indo-Pak relations improve, Pakistan can devote more attention as well as military resources to fighting the extremists in the tribal areas. This also reduces the scope for the Punjab-based militant groups to mobilize support by playing up India’s strident disposition towards Pakistan. According to Dr. Rizvi, “Improved India-Pakistan relations will help to fight terrorism.”

This material does not reflect the views of the Jinnah Institute, its Board of Governors, Board of Advisors or the President.

This material may not be copied, reproduced or transmitted in whole or in part without attribution to the Jinnah Institute (JI). JI publishes original research, analysis, policy briefs and other communications on a regular basis; the views expressed in these publications are those of the authors alone. Unless noted otherwise, all material is property of the Institute. Material copywritten to JI: Copyright © 2010 Jinnah Institute Pakistan under international copyright law.