Policy Brief

Leave No One Behind: Including Women in the Afghan Transition

by: Ammara Durrani

Date: June 11, 2020

“Some members of the Taliban delegation were looking at me. A few were taking notes. Some others were just looking elsewhere…Since our side had women delegates, I suggested to them [the Taliban] that they should also bring women to the table. They laughed immediately[1].”

– Fawzia Koofi, Vice President of Afghanistan National Assembly, Politician & Women’s Rights Activist

The Game’s Deep End: Violence Eroding Political Agency

The end-game in Afghanistan has moved to the deep end of a 42-year continuum of violence. The trumpeted peace pact on February 29th between the United States and the Taliban was followed by a bloodbath that impacted innocent civilians as much as Afghanistan’s warring factions. Progress on the envisioned Intra-Afghan negotiations between President Ashraf Ghani’s administration in Kabul and the Taliban has lurched from one stalemate to another. Even in the face of an all-consuming COVID-19 pandemic, global calls for a ceasefire were rejected. It is obvious that power brokers do not consider the pandemic a serious factor in their overall strategic decisions.[2] Afghanistan remains a blood-soaked arena waiting to be governed by brute force – albeit where the foreign occupier has cut its losses and declared a withdrawal to minimise its own casualties through “reduction of violence”. The battleground remains open for Afghan forces and militant groups to resume an extended fighting season.

In 2018, a Jinnah Institute publication highlighted a positive correlation between Afghanistan’s peace prospects and the inclusion of its women in any power sharing mechanism, and concluded that a unilateral US-Taliban deal – struck exclusively from the prism of military security – may intensify a violent power-grab for Kabul, and whose domestic free-fall will undo the nurtured fabric of fledgling socio-economic governance and citizenship in the country.[3] The current anarchic situation has proven that argument. The American nation-building project in Afghanistan has come full circle. Afghans find themselves standing once again on the existential precipice of stark political choices that will determine everyday survival: to be ruled by the Taliban or not? The UN and regional quad of Russia, China, Pakistan and Iran have sounded the global call[4] for an immediate ceasefire in the face of a sharp rise in civilian casualties[5] that violate international law.

Afghanistan’s continuum of violence is reversing the hard-earned socio-political, economic and institutional agency of its population and civil society, of whom women are frontline leaders and practitioners. Women did not take up arms in Afghanistan by conscious choice. They adopted the slow and perilous path to political agency for achieving rights, freedoms, and opportunities. Despite their relative strength gained from 2001 onwards, Afghan women are today still crying out for their survival, for their children, families, and communities. They rightly ask: when violence is their only reality, what kind of future can they hope for?[6]

This policy brief analyses the current state of play for Afghanistan’s ‘woman question’. It does not deep dive in the state of women’s structural empowerment, since that aspect has been recorded in the 2018 paper referenced above and in other literature produced since then. Rather, taking the February 29th deal and its ensuing politics as the main context, this brief looks at the responses responses by primary stakeholders towards this issue and where they stand to impact the larger peace process. Unbridled violence is eroding women’s hard-won agency, and a political process without women will ultimately fail to create the ‘Afghan-led and Afghan-owned’ peace desired by all. To demonstrate that a peace deal need not become a reductive choice between power-centric traditional security concerns and real human needs, a practical road-map is further suggested comprising of immediate and mid-term policy interventions by primary stakeholders that will prevent the reversal of positive gains and enable them to make the process effective, representative and sustainable.

Oblivious to the Pandemic

For ordinary Afghans, the spiral of violence has had no let-up despite the COVID-induced suffering that transcends borders, and which has upended the global political economy. Afghans are forced to confront the double jeopardy of COVID-19 alongwith increased violence, and its disastrous impact on the country’s fragile economy and socio-political setup. More than half of Afghanistan’s population now lives below the poverty line despite billions of dollars spent in international aid. Significantly for women, an estimated 2 million widows are struggling to make a living.[7] The rate of women’s employment is a fraction of that of men, with only about a fifth of women in the labour market and an unemployment rate of 67% for women seeking work, according to 2018 Gallup data.[8] Women’s participation in the labour force, already threatened by militant groups and hostile social attitudes, has been cut back by the pandemic wreaking economic havoc with job losses all over.[9]

In such a political economy, the case for women’s role in Afghanistan’s peace, reconciliation, governance and nation-building processes is already established and accepted by all stakeholders except the Taliban. International and regional forums have dedicated spaces for Afghan women as vibrant dialogue participants and decision influencers, while reiterating[10] their value as necessary catalysts for achieving negative peace and transitioning to positive peace in the long run.[11] Since 2018, and during the months leading to the February 29th US-Taliban pact, the subject of Afghan women, peace and security has gained more traction in multilateral debates on peacebuilding in Afghanistan.[12]

Women were given their rightful representation in various Intra-Afghan dialogues held through 2019-2020 (in Doha and Moscow), and commendably, in the state-level nomination for Kabul’s 21-member official team (comprising of five women) mandated to undertake impending negotiations with the Taliban this year.[13]

A bird’s eye view of current ground political realities yields key trends that will determine the ultimate end-game and its impact on women’s future. Firstly, there is an obvious reduction in intensive policy engagement by the US, and downscaling of large financial investments despite criticism at home.[14] Talk of residual counter-terrorism operations and commitment to defend Afghan forces against terror attacks (including those by the Taliban) are running in parallel, but its actual play-out remains unclear. This is primarily because both the US and Taliban are following their mutual commitments by no longer targeting each other. Failure to do so will mean reverting back to square one, which neither party wants.

This positive movement beyond the zero-sum game brings more salience to the domestic intra-Afghan contest. The cards are stacked in favour of the Taliban who usually hold an uncompromising position about negotiations with Kabul. Conversely, President Ashraf Ghani’s administration – despite its international legal legitimacy, financial support, governance paraphernalia and national army – remains a patchwork of executive power coordination and policy gridlocks. A ceasefire is currently in place since Eid between both sides that has seen a fall in civilian casualties by 80 percent, but the Ghani administration can’t wish away its grave political divisions, corruption and weak governance, increasing military defections, and incapacity to police and counter militant violence.

In this male-dominated milieu, there is a real possibility that women’s meaningful participation may become sidelined or ignored in the crucial negotiations that will hammer out a constitutional and governance framework. The Taliban rejected President Ghani’s negotiation team and a new power-sharing agreement signed in May between President Ghani and Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, Chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation (HCNR), will likely herald its new composition.[15] Their agreement outlines the framework for joint governance as well as modalities of negotiations with the Taliban. But it only references women alongwith other population segments. Observers were dismayed to note the absence of women in the high-profile ceremony at the presidential palace on May 17th. The Kabul administration may be taking women’s role for granted, and both President Ghani and Dr. Abdullah need to be reminded of Kabul’s institutional commitment for women’s empowerment. It is commendable that Dr. Abdullah Abdullah has ensured women’s participation in the subsequent HCNR preparatory meetings held during May-June for negotiations with the Taliban. However, the nature and substance of women’s participation in these meetings remains unclear.

A worst-case scenario is Afghanistan descending into an indefinite vortex of Kabul-Taliban violence aided by gruesome Islamic State attacks, as well as proxy wars between the Gulf rivals (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Qatar), Pakistan, India and other actors.[16] For women leaders and practitioners both within and outside Afghanistan, the first two scenarios create ingress for strategic and tactical interventions to partake in the peace process. But if the proxy war scenario takes over, that will end their space and agency.

Beyond the ‘woman question’, a ceasefire is no longer just a moral imperative. It has become a strategic necessity for all major stakeholders – especially the Trump administration and the Taliban – who have moved from their original positions and are investing in dialogue. In the eyes of their respective constituencies, interlocutors, investors and patrons, unabated violence erodes their legal and institutional credibility in establishing peace.[17]

The Fear Factor: Can the Taliban Change?

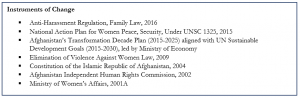

The Taliban’s official stance holds that women can work and be educated, but only within the boundaries of Islamic law and Afghan culture.[18] It does not entail democratic freedoms and opportunities that the new and urbanised generation of Afghans has become used to as an integral part of life. Fear of these opportunities quashed by a prospective Taliban government drives women and civil society to demand their space on negotiating tables, in governance, and in law. Experience in politics and government is making women assert themselves even in crises. For example, right after the barbaric attack on a maternity ward in Kabul last month, Deputy Interior Minister, Hasna Jalil, forcefully defended her office and women security officials in the face of a social media backlash and threatened legal action.[19] This kind of existing institutional strength of women in Afghanistan’s governance structures is crucial for any government to leverage, the Taliban included. But from a tactical and strategic view of the peace process’s politics, it is equally necessary that women set out a clear, detailed and segmented charter of demands that is more than a generic call to action. The term “meaningful participation” often appears unclear, especially to their male counterparts. Their asks need to be fleshed into specifics of how participation is structurally implemented with quantifiable objectives, metrics, and outcomes. A good example is the four-point proposal released by the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission.[20] Though not specific to women’s issues, it sets out a structured approach for addressing human rights issues in the current peace process. There is a need to create a similar structured model for negotiating women’s rights and roles in the process.

The Taliban have not offered a revised position on women’s presence in public life. But their recent responses – on community health measures for COVID-19 in areas under their control, as well as condemnations of the Kabul maternity hospital attack – try to refurbish a ‘humanitarian’ brand and reflect a modernist approach. In a rare interview given to a New Delhi-based think-tank, Taliban Spokesperson Suhail Shaheen reiterated his group’s proclaimed commitment to women’s education. When pressed on the question of women’s participation in their delegation for the Intra-Afghan negotiations, he exclaimed with a smile, “Anything is possible!”[21] In a further development, Taliban Supreme Leader Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada issued an inclusive message of general amnesty ahead of Eid ul Fitr: “Every male and female member of Afghan society shall be given their due rights, as none shall feel any sense of deprivation or injustice… All work necessary for the welfare, durability and development of society will be addressed in the light of divine Shariah law.”[22] Calling it a “critical opportunity” for peace, this statement also lays out the Taliban’s current thinking on foreign policy, international affairs and related issues.

Notwithstanding the insistence on Shariah as their core legal framework, these developments indicate that the Taliban may well be concerned about an ostensible failure to safeguard Afghan women and for being castigated on human rights. Recent evidence shines a light on the Taliban’s relative successes in justice mechanisms for women.[23] Combined with a newfound internationalist attitude, these could serve as openings for their constructive engagement on women’s issues. Their supporters and interlocutors must take it up as a joint policy agenda ahead of the Intra-Afghan negotiations. In recent years Saudi Arabia, under the leadership of Crown Prince Muhammad Bin Salman, has demonstrated remarkable progress for initiating civil society reforms, including empowerment of women and youth. Similar pro-women policies have been initiated by the UAE and Qatar. The Gulf States have set precedents by appointing qualified women to represent their countries in strategic bilateral and multilateral foreign policy, security, business, and civil society forums. Pakistan along-with other Muslim countries can assist in carving out a women’s empowerment agenda for governance in line with universal Islamic principles and provide intellectual, institutional, technical, and vocational support.

Pakistan’s Strategy: Need to Humanise Policy Footprint

As a primary actor seeking positive outcomes in Afghanistan’s present and future, Pakistan’s engagement with the peace process shows concerted steps to protect traditional security and foreign policy interests.[24] Islamabad’s approach in leveraging economic cooperation, regional integration and connectivity through transit trade routes, infrastructural support and construction of special economic zones holds promise, but also reflects Cold War era thinking. On the whole, Pakistan’s policy responses fall short of holistic, full-spectrum engagement that privilege human security and empower women, youth, civil society and parliaments. By limiting state response to tribal management of the Taliban and reacting to Kabul’s hostile policy statements, decision-makers in Pakistan have ceded legitimate space to adversaries, and squandered any dividends of soft power owing to poor civic imagination and disconnect with local communities.

Is Pakistan part of the human security conversation with Afghanistan? Not really. Its posture lacks a human face, agency and content that are defining characteristics of 21st century soft power and public diplomacy. Pakistan has decades of relevant governance and human development experience, tools, capacities, and value propositions to bring to the table. Its women’s rights movement has had a remarkable history and record of bringing about sustained social, political, economic, institutional, and legal reforms and transformations in the face of daunting barriers that are very similar to the ones that Afghan women face. Yet, Pakistan is not leveraging these to become Afghanistan’s development partner. Compared to India’s $3 billion development assistance to Afghanistan that enjoys high-visibility and appreciation, public knowledge is minimal about Pakistan’s $1 billion (mostly brick-and-mortar, and now ending) development assistance. Official websites of our Foreign Office and Kabul Embassy leave much to be desired. There are too few exchanges and collaborations between parliamentary, civil society, academic, scientific, arts and media communities; youth and women leaders; entrepreneurs; and legal and business groups between our countries. The existing ones have been initiated by civil society organisations and funded by international donors. These are the actors and groups who will reduce the trust deficit, bring ‘normalcy’, development, growth and employment that both countries desperately need. Furthermore, the coronavirus pandemic has put people’s needs right at the centre of policy agendas.

Islamabad fails to read both text and sub-text of the woman question and its high strategic importance in Afghanistan’s end game. Because of an invisible public diplomacy profile, most people on both sides of the border do not even know who Islamabad’s ambassador in Kabul is. This is a high-value and high-visibility space with long-term dividends that Pakistan needs to build on. Pakistan’s negative image and perception in Kabul stands a good chance of improvement by appointing a dynamic woman leader as “our man in Kabul”, who can catalyse development and cultivate people-to-people interactions to create more substance in Islamabad’s peace efforts. It is time to install leadership in the Kabul Embassy that is well versed with 21st century framing and resources of soft power and conflict transformation to maximise leverage. A strategic balancing act in consonance with Gulf partners, the Taliban as well as the Kabul regime, on soft power initiatives such as women’s empowerment will minimise Islamabad’s political risks and elevate its foreign policy profile.

Policy Recommendations for Primary Players

The coronavirus pandemic has occasioned a global debate on the world’s future post-COVID. The arguments for pursuing value-based international cooperation and multilateralism outweigh moves towards insular protectionism.[25] South Asia is certainly no exception to this dynamic. The European Council’s detailed and stern statement has called upon Kabul and the Taliban to ensure that rules- and rights-based negotiations take place for international financial support to continue.[26] The Afghan conflict offers a clear and present opportunity for stakeholders to program a framework for women rights and test this international pledge. The following set of policy ideas for primary stakeholders can be a good starting point.

For Pakistan

- Demilitarise and humanise the bilateral relationship in tandem with our geo-strategic and security concerns. Create a consultative five-year Strategic Plan for a full-spectrum bilateral engagement with Afghanistan that lays out clear goals, objectives, actions and partners. It should be inclusive, focused on human security, and demonstrate a committed gender value proposition for both countries. It should entail up-gradation of our on-line and off-line public diplomacy and strategic communications apparatus, tools, and resources.

- Initiate dialogue with Kabul to appoint respective women ambassadors in Islamabad and Kabul who can leverage public diplomacy to induce trust and vigour in people-to-people, human development, and business linkages. This can be an excellent CBM and bilateral goodwill gesture by both countries. Both countries already have women ambassadors in other diplomatic posts.

- Press upon the Taliban to undertake ceasefire, and include women in negotiations to win local, public and international support. Build their technical capacities and facilitate dialogues between the Taliban and women leaders/practitioners for joint working mechanisms and collaborations. Elicit support from the Gulf States, China, Russia, Iran and CARs for such initiatives.

- Reminiscent of Pakistan’s leadership of the Second Islamic Summit Conference in 1973, organise an Islamic Women’s Empowerment Colloquium in Islamabad that brings together Taliban, Kabul, regional and international players, women leaders, private sector members for dialogue on women’s role in the future of Afghanistan. The event could result in the formation of a representative International Muslim Women’s Council.

- Encourage and empower National Assembly and Senate to review and pursue Pakistan-Afghanistan parliamentary caucuses. Existing parliamentary caucuses for women and youth must be leveraged better. The newly established joint Qatar-UN platform for empowering parliaments for conflict resolution, mediation and counter-terrorism should be requested to support such initiatives.

- Initiate and support robust Track II initiatives, roping in policy actors and influencers who can create space for new ideas. Civil society (especially women and youth), private sector, and media should be encouraged to create grassroots opportunities, as both governments are resource-strapped.

For Taliban

- Undertake immediate ceasefire and adopt a non-violent path to negotiation. Continued violence is counter-productive for gaining the support of citizens. Demonstrate governance capacity, win opportunities for political mainstreaming, and sit at multilateral forums.

- Include women interlocutors in upcoming negotiations. Continue and intensify dialogues with women leaders for understanding and addressing their concerns through mutual learning and negotiation, and demonstrate that they will not block rights for women.

- Understand that all military victories must follow transitions towards positive peace through engagement and collaboration with communities. Women are valuable allies in governance that has credibility and legitimacy.

For US, Allies, and Multilateral Forums

- Tie existing and future political, economic, and security support to Afghanistan with inclusion and leadership opportunities for women in peace and rebuilding processes, regardless of who wins power. Power and legitimacy must be made synonymous with inclusion.

- Encourage and support the Gulf States, Pakistan, and the Taliban to take ownership of the women’s agenda as their own, rather than as a Western idea that is perceived to clash with Islamic and local cultural values.

- Intensify support for civil society and multilateral initiatives on WPS (women, peace & security) in Afghanistan and across the region, especially engaging Pakistan, Gulf States, Iran, CARs, multilateral agencies, and private sector actors. Focus on research and capacity-building initiatives for negotiations, peace-building and reconstruction processes that place women at the centre.

For Women-Led Groups in Afghanistan and Pakistan

- Demonstrate neutrality and openness to engaging with the Taliban for the primary objective of enabling cessation of hostilities and peace-building. Incremental gains are easiest to sustain and useful to build on.

- Draw up a detailed charter of demands and plan of action that reflects clarity of purpose and offers tangible methodologies and solutions.

- In Afghanistan-Pakistan Track II dialogues, move past statist positions that perpetuate conflict, trust deficit, and hatred. Bring alternative ideas to the table, and demonstrate capacity to work with all conflicting sides. Be the bridge-builders and peacemakers that women have been for decades within Afghanistan and Pakistan.

- Unify collective efforts and voices; intensify advocacy and ground action. Reach out and network with all women ambassadors, foreign ministers, parliamentarians, and judges of the world to create a global coalition calling for women’s inclusion and interests in the peace process.

- Increase people-to-people initiatives, especially for research, advocacy, political activism, business activities and diplomatic initiatives for furthering your agenda.

After nearly 19 years of counter-terror experience in Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria, US military strategists now believe that the rise of militancy and its sustained foothold in ‘global borderlands’ like Afghanistan occurs due to weak state presence and governance incapacities. Foreign military deployments cannot resolve these problems, and local populations need to develop and administer systems of governance themselves.[27]

The dicta of ‘Afghan-owned, Afghan-led’ peace process and ‘no military solution’ lose meaning if the Afghan people, women included, are not placed at the centre of the peace process. A meaningful agenda for policy negotiations on governance, human security and development of Afghanistan should replace the long continuum of violence that Afghanistan has suffered from for three decades. As this piece was being written, the Taliban have expressed willingness to resume dialogue with the Kabul government. There is hope at long last that the peace will not lapse into more murderous violence.

____________________________________________

The author is a public policy professional with 19 years of expertise in conflict, peace and human security work for government, bilateral and multilateral actors. She is an advocate for mainstreaming women in foreign policy and security paradigms. Tweets: @ammaradurrani.

____________________________________________

REFERENCES

[1] Nataranjan, Swaminathan, “Afghan peace talks: The woman who negotiated with the Taliban”, BBC World Service, February 27, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-51572485.

[2] To date, the COVID-19 caseload for Afghanistan stands at 7,650+ cases with 175+ deaths, out of a total population of more than 38 million: Worldometer, May 20, 2020, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/afghanistan/.

[3] Durrani, Ammara, “The Woman Question: Gains at Risk”, War & Peace: The Afghanistan Essays, Jinnah Institute, Islamabad, January 9, 2018, https://jinnah-institute.org/publication/the-afghanistan-essays-the-woman-question-gains-at-risk/.

[4] Joint Statement by the Special Representatives on Afghanistan Affairs of Pakistan, China, Russia and Iran, May 18, 2020, http://mofa.gov.pk/joint-statement-by-the-special-representatives-on-afghanistan-affairs-of-pakistan-china-russia-and-iran/.

[5] UN’s April 2020 figures indicate an increase of 25% compared to April 2019 and at similar levels as March 2020. “Rising civilian casualty numbers highlight urgent need to halt fighting and re-focus on peace negotiations”, United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan, May 19, 2020, https://unama.unmissions.org/rising-civilian-casualty-numbers-highlight-urgent-need-halt-fighting-and-re-focus-peace-negotiations. According to Cost of War Project of Brown University, more than 157,000 people have been killed in the war since 2001, and more than 43,000 of those killed have been civilians, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/civilians/afghan.

[6] Afghan Women’s Network, “Open Letter to Her Highness Sheikha Moza Bint Nasser, Queen of Qatar”, The Coalition of “Our Voice Our Future in Afghanistan”, May 2, 2020, https://twitter.com/AWNKabul/status/1256536712811077633?s=09.

[7] Op. Cit. BBC World Service, February 27, 2020.

[8] Hakimi, Orooj, “Afghan airlines at risk of collapse, taking women’s jobs with them”, Reuters, May 4, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-afghanistan-airlin/afghan-airlines-at-risk-of-collapse-taking-womens-jobs-with-them-idUSKBN22O0GR?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=twitter.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “Joint Statement on Women’s Inclusion in Afghanistan Peace Process” by Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, U.K. and E.U., June 4, 2020, https://twitter.com/AusEmbAfg/status/1268421756378771457.

[11] “Qatar stresses need for involving women in Afghan peace process”, Gulf Times, May 10, 2020, https://m.gulf-times.com/story/662853/Qatar-stresses-need-for-involving-women-in-Afghan-peace-process.

[12] Examples include a consistent body of research and literature produced by the United States Institute of Peace, such as Humayoon, Haseeb & Basij-Rasikh, “Afghan Women’s Views on Violent Extremism and Aspirations to a Peacemaking Role”, February 3, 2020, https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/02/afghan-womens-views-violent-extremism-and-aspirations-peacemaking-role. Also see “What Will Peace Talks Bode for Afghan Women?”, Briefing Note/Asia, International Crisis Group, April 6, 2020, https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/south-asia/afghanistan/what-will-peace-talks-bode-afghan-women.

[13] “Afghan government unveils negotiating team for Taliban talks”, Arab News, March 27, 2020, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1648411/world.

[14] For end-game debate within the U.S., see Ryan, Missy, “For most of Afghanistan war, U.S. ‘never really fought to win,’ Trump declares”, The Washington Post, May 19, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/for-most-of-afghanistan-war-america-never-really-fought-to-win-trump-declares/2020/05/18/9ab85afa-992c-11ea-b60c-3be060a4f8e1_story.html.

[15] Mashal, Mujib, “Afghan Rivals Sign Power-Sharing Deal as Political Crisis Subsides”, The New York Times, May 17, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/17/world/asia/afghanistan-ghani-abdullah.html. See transcript of agreement here: https://twitter.com/atanzeem/status/1261989185872973824.

[16] For a good analysis of historical and contemporary power tussle as well as competing interests of the Gulf states in Afghanistan, see Bodetti, Austin, “Which Middle Eastern Power Will Win in Afghanistan?”, Inside Arabia, May 8, 2020, https://insidearabia.com/which-middle-eastern-regional-power-will-win-afghanistan/.

[17] For a domestic backlash critique of the U.S. agreement with the Taliban and its wider repercussions on American foreign policy, see Rubin, Michael, “Desperation for Afghanistan peace deal creates dangerous precedent”, Washington Examiner, May 16, 2020, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/desperation-for-afghanistan-peace-deal-creates-dangerous-precedent.

[18] Op. cit. Durrani, The Afghanistan Essays, 2018.

[19] Kakar, Javed Hakim, “Unfair criticism may have criminal consequences, warns Mrs. Jalil”, Pajhwok Afghan News, May 17, 2020, https://www.pajhwok.com/en/2020/05/17/unfair-criticism-may-have-criminal-consequences-warns-mrs-jalil?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter.

[20] “The Peace Process Beyond the Negotiating Table: A proposal to engage victims, experts, and the broader public in the Intra-Afghan Peace Process”, Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, June 2, 2020, https://www.aihrc.org.af/home/daily-reports/8885.

[21] “Exclusive Conversation by Afghan Taliban Spokesperson-Mohammed Suhail Shaheen in GCTC Manthan,” Global Counter Terrorism Council, India, April 23, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDzc_R-avGo&feature=youtu.be.

[22] “Taliban supreme leader offers general amnesty to opponents”, Dawn, May 21, 2020, https://www.dawn.com/news/1558651/taliban-supreme-leader-offers-general-amnesty-to-opponents.

[23] Jackson, Ashley and Weigand, Florian, “Rebel rule of law: Taliban courts in the west and north-west of Afghanistan”, ODI Humanitarian Policy Group, Briefing Note, May 2020, https://www.odi.org/publications/16914-rebel-rule-law-taliban-courts-west-and-north-west-afghanistan.

[24] Hussain, Touqir, “Ending Afghanistan’s Endless War: The Pakistan Factor”, The National Interest, May 10, 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/middle-east-watch/ending-afghanistan%E2%80%99s-endless-war-pakistan-factor-152691.

[25] Malley, Robert, “The International Order After COVID 19”, Project Syndicate, April 24, 2020, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/pandemic-nativism-versus-globalism-by-robert-malley-2020-04.

[26] “Council adopts conclusions on the Afghanistan peace process and future EU support for peace and development in the country”, May 29, 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/05/29/council-adopts-conclusions-on-the-afghanistan-peace-process-and-future-eu-support-for-peace-and-development-in-the-country/.

[27] Depetris, Daniel, “No, ISIS Isn’t Resurging Amid the Coronavirus Pandemic”, Defense One, May 15, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2020/05/no-isis-isnt-resurging-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/165401/?oref=DefenseOneTCO.