Policy Brief

Electoral Reform and Women’s Political Participation

by: Sabina Ansari

Date: August 8, 2011

Overview

Pakistan is in urgent need of electoral reform. Currently, there are a number of pressing domestic issues that are seemingly of higher priority for national and international stakeholders, such as the widespread devastation caused by the flood, the economic downturn, and rising extremism. With the general election approaching in 2013, and the recent adoption of the 18th amendment by Parliament, it is crucial that stakeholders turn their attention to reforming a weakened and flawed electoral system in order to support democracy and national stability. There are various aspects of electoral reform that require attention. This paper examines electoral reform as it pertains to the political participation of women with regard to exercising their right to vote.

Problems with the Electoral Process

A number of factors have seriously undermined the integrity of Pakistan’s electoral process over time. Widespread electoral fraud has eroded democratic development, political stability and the rule of law. Successive military governments have manipulated national, provincial and local polls to centralize power within the military and its allies. Highly inaccurate voters’ lists and poorly managed polling stations are responsible for disenfranchising millions, especially women. Polling procedures and codes of conduct are often blatantly disregarded with no consequences for the offenders. Dysfunctional and corrupt election tribunals have proven incapable of resolving post-election disputes. Such factors affect all constituents, but are amplified in the case of marginalized citizens such as women and religious minorities.

These patterns have also compromised civilian institutions such as the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), which is responsible for overseeing credible elections and orderly political transitions. The commission suffers from a lack of resources and poor management, which has affected its capacity to research and analyse past elections and to raise important electoral issues. It has had several problems with maintaining an accurate and healthy electoral roll. While it is addressing that problem, the ECP has also been documented as being insensitive to the needs of women voters, and is itself characterized by an extremely low number of women employees, with none in senior management. At present, out of a total nationwide employee count of 1800, there are merely seven women in ECP regional offices: one in Islamabad, one in Punjab, two in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, two in Sindh, and one in Balochistan.

If the current government completes its five-year term, the next general election will be held in 2013. A flawed election will pose a serious threat to Pakistan’s already shaky stability. A new population census, originally due in 2008, is scheduled for August-September 2011, presumably followed by a large-scale redistricting exercise. In the current climate, a flawed census, gerrymandering, or a rigged election could create nationwide political violence. Now is the time to lay the framework for a transparent, orderly political transition through free and fair elections, and, in keeping with Pakistan’s international commitments to achieving gender equity, ‘free and fair elections’ must include the robust political participation of women.

Barriers to Women’s Political Participation

Although the constitution of Pakistan guarantees dignity, freedom and equality to all citizens and forbids discrimination on the basis of sex, women remain marginalized in various aspects of public participation. This includes political participation, both in terms of holding office and voting. Not only do women face formidable barriers to entry in the public sector, they are exceedingly disenfranchised, eroding their political stake and diluting their political power. Women are under-registered in electoral rolls, face opposition when trying to vote, and are turned away from the polls.

Pakistan’s electoral rolls leave much to be desired in terms of accuracy. According to reports, electoral rolls still contain names of the deceased, expatriates and people who have moved out of the constituency. The ECP is aware of these problems, and is currently in the process of vetting and updating the electoral rolls with the collaboration of the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA). This is important, particularly with regard to women, since several instances of malpractice or denial of the right of franchise can be attributed to errors on the electoral rolls.

There has been a general downward trend in the overall voter registration and turnout in Pakistan. The ECP does not maintain gender-disaggregated data in this respect, but various regional and provincial studies document an increasing trend of low turnout of women voters.

In the 2002 elections, 71.86 million people were registered as voters. Based on a population growth rate of 2.7 percent per annum, registered voters were projected to number 88 million in 2007, but the ECP issued a list of only 56 million eligible voters. Women took a proportionally larger hit of this decrease in registration (39 percent as compared to 18 percent for men). Even though almost half the eligible voters in the country are women, there is a significant disparity between the number of women and men registered on the electoral rolls. Women shrunk to 30 percent of total voters in 2007, as opposed to 40 percent in 2002, reflecting a difference of over 6 million. The decrease in women voters by province/territory between 2002 and 2007 is as follows:

Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa: 45%

FATA: 85%

Sindh 41%

Punjab: 37%

Balochistan: 36%

Islamabad Capital Territory: 19%

The highest number of unregistered women in 2007 was in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa followed by Sindh, Punjab, and Islamabad.

The declining trend in the turnout of all voters may indicate growing disillusionment and a lack of faith in the political system due to constant corruption. There are several reasons for a low turnout of female voters. Deeply entrenched patriarchal values, supplemented by discriminatory legislation, inadequate policies, programs and budget allocations, may be part of the reason. Women in remote rural and tribal areas, for example, depend on the men in their families for access to resources, transportation and basic civic amenities such as the National Identity Card (NIC). They are routinely prevented from exercising their right to vote by their families, tribes, clans, and local and spiritual leaders, sometimes with threats to their physical wellbeing.

Election officials, willingly or otherwise, also appear complicit in disenfranchising women and being insensitive to their needs. For example, polling stations have insisted on veiled women showing their faces for identification to male polling staff, which discouraged some women from voting. In certain areas, election officials blatantly flouted ECP regulations and barred women from voting, and when the ECP tried to intervene, local community leaders threatened to boycott the by-election based on their assertion that the political participation of women was contrary to their values.

Finally, the political parties have not helped. In some constituencies, particularly in Balochistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, rival candidates and political parties have engineered mutual agreements to restrain women from casting their votes. Some cases escalated to the point that local police was summoned and polling was halted.

Several reports detail instances where election officials, election candidates and political parties barred women from voting:

During the local government elections in 1950-60, two candidates reached an agreement to bar women from voting in the Pai Khel Tehsil of Mianwali. This agreement is still in effect: there are only 6,000 women voters in a population of 30,000.

In 1993, in a settled district of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, candidates from PPP and ANP, as well as an independent candidate, signed an agreement with each other and village elders to disallow women from voting.

In some areas in Bajau, Mohmand, Khyber, Orakzai and North Waziristan Agencies of FATA, not a single female vote was cast in the 1997 elections. In Jamrud, only 37 out of 6,600 registered women voted.

An observer team from South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in the 1997 election noted that women were physically stopped from voting in Balochistan.

In one village in Punjab, women were granted the right to vote for the first time in 1998, almost 30 years after the introduction of universal adult franchise in the country.

During the local government elections in March 2001, more than 13 out of the 56 union councils of Swabi barred thousands of women from casting votes after contesting candidates signed an agreement. The local jirga members, religious parties and even members of major political parties were part of the agreement.

Due to a faulty and/or fraudulent electoral roll, the ECP denied voting rights to 38 million people—mostly women—for the November 2007 elections.

Women were barred from voting in the NA-28 by-election in Buner on December 28, 2008. In addition, women were completely prevented from voting at more than one-fourth of all polling stations. According to the ECP, 18,939 women registered at 35 polling areas. All of them were disenfranchised.

In 2008, only 0.4 percent of Display Centre Information Officers (DCIOs) were female, and there were no separate areas at any of the Display Centres for female eligible voters to receive assistance in filling out the necessary ECP form to add their names to the electoral roll. The incidence of DCIOs helping women fill out their forms was only 11 percent.

Almost 95 percent of registered women voters in Musakhel were disenfranchised during the by-elections for PB-15 of the Balochistan Assembly on November 11, 2010. Female registration was already low at 40 percent.

Although there are penalties and legal redress for such acts, no action has been taken against the perpetrators, despite the outcry from several national and international agencies. The lack of political will and the absence of effective affirmative action allow such disparities and injustices to flourish.

Furthermore, women face strong barriers to holding public office, which in turn bolsters the marginalization of the female constituency. By denying the right to political participation to millions of women, the government of Pakistan is oppressing half its sovereign constituency while strengthening regressive, misogynistic forces, and violating charters of human rights to which it has acceded.

Steps in the Right Direction

There have been recent advances to democratize and regulate the electoral system in Pakistan with attention given to enhancing the participation of women.

The Gender Reforms Action Plan (GRAP) was launched in 2002 and concluded in 2010. GRAP’s directive was gender mainstreaming, i.e., ensuring that all public sector policies and projects at the provincial and federal level include gender perspectives and promote equality between men and women. Objectives included the political empowerment of women, which entails electoral, administrative and institutional reforms to achieve gender equity in the public sector. As an integral part of the government’s efforts to address gender inequity, GRAP has provided a framework for institutional restructuring of the public sector.

Pakistan signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in 2008, which obliges it to ensure free and fair elections under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The covenant affords equal rights to all citizens to participate in public affairs, including suffrage and public office.

The constitutional distortions wrought by the 17th Amendment were repealed in April 2010 when both houses of Parliament unanimously passed the 18th Amendment and introduced provisions to strengthen parliamentary democracy. The amendment enhanced the ECP’s independence by making the appointment of its key officials more transparent and subject to parliamentary oversight. The chief election commissioner and other ECP members, previously appointed by the president, will now be selected through consultations between the prime minister and the leader of the opposition in the National Assembly, and subsequently vetted and approved by a joint parliamentary committee comprising, equally of government and opposition members.

The ECP has taken some steps toward electoral reform. In May 2010, it produced a strategic five-year plan with significant international assistance, listing fifteen broad electoral reform goals divided into 129 detailed objectives with specific timeframes. These range from improvements in voter registration and election dispute management procedures to the creation of a comprehensive human resource policy. The parliamentary appointment of a new chief election commissioner and secretary of the ECP may be a ray of hope for the creation of reliable electoral rolls. ECP has also acknowledged its low number of women employees and is recruiting women to reach its stated goal of 10 percent women employees.

In February 2010, NADRA signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN), under which NADRA is responsible for identifying areas low voter registration, and FAFEN will run the public mobilization campaign to increase registration to 100 percent. NADRA has considerable technical resources to aid in database management and computerized electoral rolls. A joint NADRA-FAFEN committee will identify, among other issues, areas where CNIC coverage is very low, especially among women. NADRA has already registered 98 percent of the male population and 71.2 percent of the female population. That brings the total percentage of the registered population to 86 percent, with 12.28 million citizens yet to be registered.

Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT) has documented a significant increase in the issuance of CNICs: as of 2010, the total number of CNICs issued was documented as 75.5 million. With CNICs being issued free of cost along with the introduction of the Benazir Income Support Programme that incentivised 3.5 million households to get CNICs for their female members, 71.2 percent of eligible women and 98 percent of eligible men have already obtained their CNICs.

The Senate of Pakistan unanimously passed The Election Laws Amendment Bill in March 2011. The bill aims to ensure the security and integrity of the database of electoral rolls and makes possession of CNIC (computerized NIC) mandatory for voting. The government has promised a comprehensive “constitutional and legal framework” for electoral reforms to ensure free and fair elections, and has stated a commitment to make barring of women voters a criminal offence.

The Way Forward

Both women and men have equality of political rights under the Pakistani constitution in terms of voting and contesting all elective offices. The Fundamental Rights in the constitution guarantee the equality of all citizens before the law and allow for affirmative action in the context of women. The Principles of Policy further state that steps will be taken to ensure the full participation of women in all spheres of national life.

Pakistan adopted the Convention on Political Rights to Women in 1952, and concrete steps were undertaken to ensure women‘s right to vote, stand for elections, and hold public office. More recently, the Ministry of Women’s Development prepared a National Plan of Action, taking the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Beijing Platform of Action as a framework. The objectives of the Ministry’s plan were to improve women‘s decision-making within the family and community, and to create social awareness and a commitment to reduce the multiple burdens of women.

Penalties do exist in laws, both the Pakistan Penal Code and the Representation of People Act, for those who threaten or prevent voters from exercising their electoral rights. The Code of Conduct for General Elections 1997 forbids political parties, contesting candidates and their workers to propagate against women’s participation.

However, the concerned authorities have taken no action in this respect even when women’s advocacy groups have brought it to their attention. Pakistan and the international community should realise that a flawed general election in 2013, if not sooner, would pose a serious threat to Pakistan’s stability. All stakeholders should immediately shift programs and advocacy to support a smooth political transition in the interest of national security and democracy. In keeping with Pakistan’s international commitments to gender mainstreaming and gender equality, it is recommended that electoral reform measures must aim at achieving a 40 percent representation of women in all public sector institutions, as well as women’s full participation in the political process.

Recommendations

Substantive progress toward free and fair elections is unlikely unless Parliament assumes political ownership over the plan, oversees its implementation, holds the ECP accountable for unsatisfactory progress, and ensures that the new census (and subsequent re-districting) is carried out in the third quarter of 2011. The state has to view gender inequity as a key issue in electoral reform, repeal all regulations that are discriminatory towards women and establish a zero-tolerance policy on all forms of political violence, especially against women voters, candidates, party activists and voters. The state also has to ensure that all domestic legislation is compliant with ICCPR obligations before the 2013 general election.

- Empower the ECP. To curtail the manipulation of the electoral process, the ECP must be made independent, autonomous, impartial and effective. It should be able to issue legally binding regulations. Partnerships and consultations between ECP and all stakeholders (legislative, political, civil, media) should be nourished. ECP must prioritise the timely implementation of the Five-Year Strategic Plan (2010-2014), and enhance accountability of voting processes, election officials and electoral candidates. The ECP should investigate and reprimand all instances of women being barred from voting or contesting elections. All results from polling stations where legal codes are violated and women barred from participating should be voided and re-polled. The ECP should also arrange for adequate security and remove all unauthorized persons from polling stations.

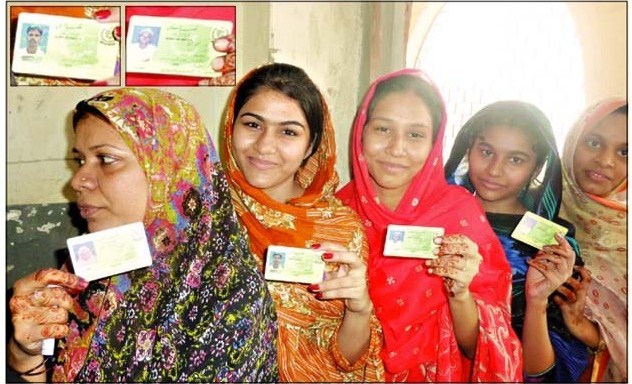

- Improve Electoral Rolls. The first element of improving the electoral rolls is to make the Computerized Electoral Rolls System (CERS) fully operational. A detailed plan for data collection should be executed by the ECP in collaboration with NADRA. NADRA’s database of CNICs should be used to improve the electoral rolls and improved voter lists should be displayed at polling stations. Bangladesh has recently institutionalised voter lists with photographs, which has allowed election staff to confirm the identity of veiled women by comparing their identity cards against voter lists. This has proven to be a successful measure, one that can be explored for Pakistan in the case of women who choose not to reveal their faces to male staff.

- Increase registration of women nationwide. A quota of at least 50 percent women as registered voters should be made obligatory for elections in any constituency. This would entail legislation, civic education, outreach, and female registration/polling staff. NADRA should ensure the continued, free issuance of CNICs, especially to women. The organization should design strategies such as automatic registration at the time of CNIC issuance, mobile registration units and postal balloting to overcome problems of access and transportation for women. The media can also be enlisted to create awareness and motivation to get women registered.

- Ensure political participation of women. The ECP should be held accountable for reaching its stated goal of 10 percent women employees. It should also employ more women in management positions and consider establishing a dedicated unit for women’s empowerment. The ECP should also disaggregate votes by gender to establish a foundation for women’s political stake and power. The GRAP framework should be utilized to its fullest extent, including inducting more women into Parliament and other public offices. Women need to be mainstreamed into political posts with strong affirmative action as opposed to the current system of reserved seats and women’s wings, which only serves to marginalize women and limit their political voice. Party manifestoes should be mandated to induct women into office and clearly articulate and implement the party position on gender equity and empowerment.

- End gender-segregated polling stations. Evidence shows that the largest female turnout is at combined polling stations as opposed to all-women stations. This might be because getting to a female polling station poses an extra hurdle for many women, and as such, it marginalizes women instead of mainstreaming them.

REFERENCES

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: Pakistan’s New International Obligations and Election Reform – Democracy Reporting International, April 2010

Pakistan’s Reservations to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – Democracy Reporting International, July 2010

The 18th Amendment to the Constitution and Electoral Reform in Pakistan – Democracy Reporting International, August 2010

Pakistan’s 2013 Elections: Testing the Political Climate and the Democratisation Process – Democracy Reporting International, January 2011

ESG Summary of Electoral Reform Recommendations for Pakistan – Election Support Group, January 2009

Draft Electoral Roll 2007: Flawed but Fixable – Free and Fair Election Network, August 2007

Intimidation and Harassment by Police and Intelligence Agencies – Free and Fair Election Network, January 2008

Security Concerns Among Voters and Candidates – Free and Fair Election Network, February 2008

FAFEN Recommendations for Electoral Reforms – Free and Fair Election Network, May 2008

Bar on women voting, terrorist attack warrant fresh NA-28 by-poll – Free and Fair Election Network, January 2009

FAFEN Preliminary Report of NA-178 By-Election Observation – Free and Fair Election Network, May 2010

Preliminary Report of PB-15 By-Election Observation – Free and Fair Election Network, November 2010

Reforming Pakistan’s Electoral Reform System – International Crisis Group, March 2011

Gender Review of Political Framework for Women Political Participation – National Commission on the Status of Women, May 2010

Win With Women, Strengthen Political Parties: Global Action Plan – National Democratic Institute, December 2003

State of Electoral Rolls in Pakistan – Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency, March 2010

Electoral Financing to Advance Women’s Political Participation: A Guide for UNDP Support – United Nations Development Programme, 2007

Report on the State of Women in Urban Local Government, Pakistan Report – United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, August 2000