After the Crisis

- by: Sherry Rehman

- Date: March 14, 2019

- Array

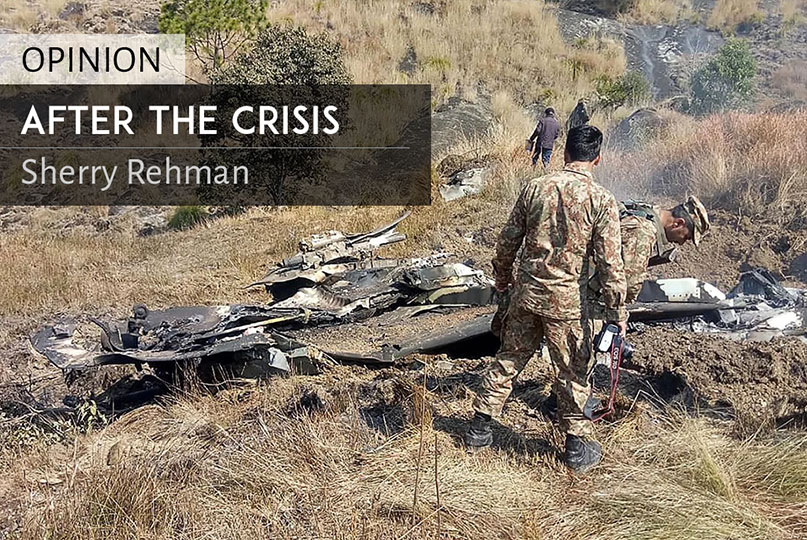

Although the 2019 India-Pakistan standoff may have passed its immediate intensity, it is clear that the entire episode has left a slew of new worries for policymakers all over the world. It is crucial that lessons are learnt and crisis-handling procedures between the two countries put in place. Because there is no doubt that Pakistan and India were perilously close to war.

In a digital age, resonating with the red noise of alternative facts fuelled by ultra-nationalisms, it was clear that the Modi regime’s need to bolster its flagging electoral ratings before an election took the Indian act of border incursion into Pakistan’s Balakot to act of war status. The second motivation was the impulse to divert attention from the growing insurgency in India-held Kashmir.

However, one outcome of the crisis sparked by the Pulwama blast is that Pakistan’s response has redefined international assessments of both the resolve and capabilities of the two countries. The second counterintuitive outcome was that Kashmir re-emerged as the most dangerous flashpoint in the world, as the Modi government ended up internationalising the Kashmir issue. The world had chosen to forget that the Kashmir dispute remains the world’s longest international dispute on the UN docket since 1948, when India’s Nehru took it to the global body to resolve its status.

Today, Kashmir has emerged as the bone of serious contention between two countries bristling with nuclear weapons. What was dangerous about its Pulwama trigger is that it brought India and Pakistan to the brink of war. Since 1971, we have never been as close to a full-scale war as we were on the night of February 28. Yet in 1971 neither country had invested in nuclear capabilities.

This 2019 standoff, therefore, brought new strategic equations and new choices to the policy mix. Faced with the unimaginable, unlike India, Pakistan united across the party divide, never losing sight of the need for de-escalation and the goal of normalisation. Amid all issues, the one point that resonated in parliament was a testament to our policy maturity. It is a truism worth repeating: Wars never resolve political disputes. If they could, Afghanistan after 17 unending years of conflict and turmoil would not be in the throes of violence today. This stands truer for countries like Pakistan and India.

The costs of war, both human and material, remain too great.

Pakistan and India have fought four wars since 1947 that have seen a combined death toll of 22,600 and 50,000 wounded and maimed. While reliable data on disappearances and civilian casualties is not available, at least 100,000 families have suffered direct human costs. The last major troops mobilisation in South Asia in 2001-02 cost the two countries a combined $3 billion.

According to a study by the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, a full-scale conflict between India and Pakistan will have unimaginable consequences. Scientists have estimated that if 100 nukes having the same size as that of the one dropped on Hiroshima are detonated, nearly 21 million South Asians will die from direct impact and half of the ozone layer will be destroyed. They estimate that the impact on agriculture from the black aerosol kicked up into the atmosphere will result in a famine of global proportions resulting in the deaths of nearly two billion people. Even a “demonstration” nuclear strike will result in 50 per cent fatalities within a five-mile radius.

While the Line of Control (LoC) in Kashmir ceasefire has all but died with artillery guns continuing to blaze since 2012, it combines with the low-intensity conflict on the Siachen glacier to result in the deaths of several hundred civilians and soldiers over the past five years. Even more have been injured, with homes shelled and communities periodically evacuated.

Despite such heavy costs in both human lives and material, both countries have drifted dangerously away from dialogue. This has been perpetuated by a misplaced Indian belief that coercion can beget dialogue only on cross-border terrorism allegedly originating from the state of Pakistan.

Based largely on Indian self-assessments of growing power, such analysis has ignored the very real conventional capabilities at play today, the resolve of Pakistan when challenged to war, and the plight of the Kashmiris. What India also chooses to ignore is the public conversation against terrorism within Pakistan and renewed steps to disrupt networks. Conversations with Delhi on how to sort through borderless challenges like dismantling militancy and climate stress issues is crucial.

While many in India argue that previous attempts at dialogue have not borne fruit, we must not let past failures overshadow our future. Pakistan does not glorify conflict. Not in the way majoritarian India does today, and not the way we used to. Having lived through more than a decade of the war against terrorism and having lost 70,000 citizens to conflict, Pakistan is very cognizant of the death and destruction caused by war. There is clarity of thought in Pakistan on pursuing normalisation, if not peace, with India. The gesture to open the Kartarpur Corridor speaks to this unanimity of thought in charting a new destiny for South Asia.

As we wake up to the very real possibilities of war, we must give dialogue another chance. A dialogue that is neither preconditioned nor selective, but a dialogue that must encompass the whole gamut of our troubled relationship. A dialogue that sees Pakistan, India and the Kashmiris as equal stakeholders in finding a path towards a brighter millennial future.

Sherry Rehman is Parliamentary Leader of the PPP in the Senate, and Chair of the Climate Change Caucus in Parliament and CPEC Committee. She has served as Pakistan’s Ambassador to Washington as well as Federal Information Minister.

A version of this article appeared in The Dawn on 14-03-2019.