Pathways to Détente

- by: Hassan Akbar

- Date: May 8, 2019

- Array

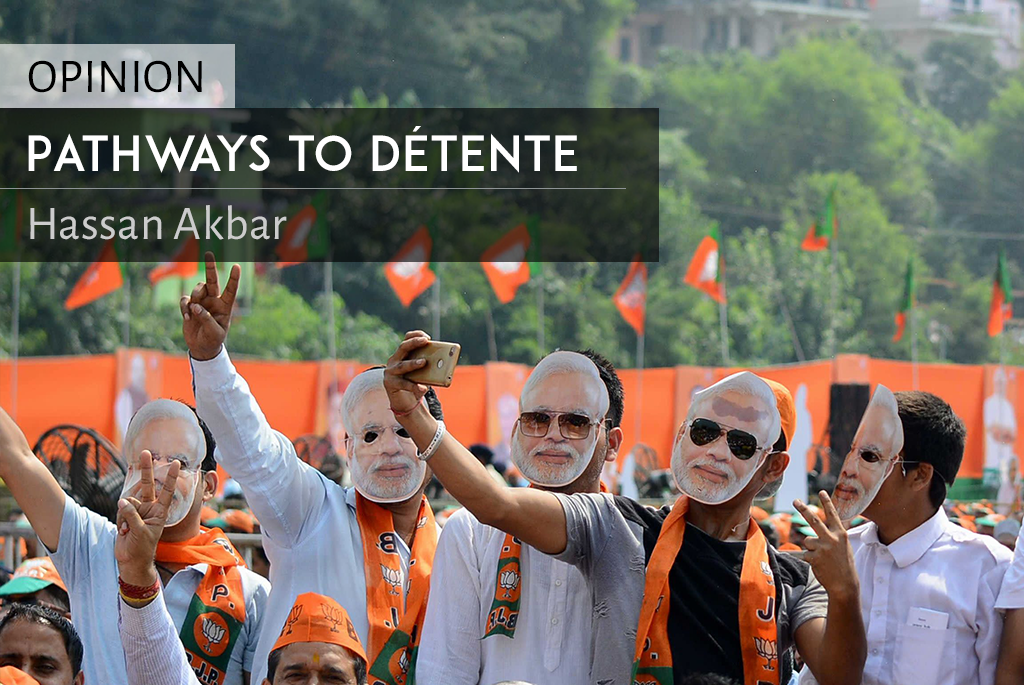

The fifth phase of voting in India’s behemoth election is over. The winner in New Delhi will shape, in part, the future of arguably the most tense bilateral relationship in the world. In Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan’s untimely remark that Narendra Modi’s re-election will provide the greatest opportunity for peace has drawn flak from the opposition.

The ground is littered with reasons to be circumspect. In a campaign season where Modi has turned Pakistan into an election piñata and gambled his political fortunes on, any expectation of peace from a BJP government is, at best, a misreading of the mood in Delhi.

The Prime Minister’s thinking is not new. For over two decades now, pundits on both sides have perpetuated a myth that peace between India and Pakistan can only be negotiated by hardline governments – BJP in Delhi and a military backed government in Islamabad. Driven by a nostalgia for Vajpayee’s “bus yatra” and Musharraf’s unilateral attempts to hammer out a solution to Kashmir through the four-point formula, the argument has rested on the premise that only the hardnosed right can sell a deal domestically without fear of backlash.

What the prime minister and others fail to appreciate is that we have been here before. In 2014, similar expectations of a breakthrough with a new BJP government delayed granting the NDMA status under an outgoing Congress government. Since then, we’ve been in a bilateral deep freeze. In his five years, Modi made only cosmetic overtures to Pakistan. Both Sushma Swaraj’s visit to Islamabad and Modi’s uninvited drop-in at Lahore were a play to an international audience, not meaningful offers for a resumption of dialogue. Instead, the BJP government has doggedly pursued an agenda of punitive action, isolation and a shifting the goal post on Kashmir and the neighborhood. Today, even the low hanging fruit in this relationship are out of reach. Trade is off the table, water has been weaponized, military action has become acceptable, and even prisoner exchanges and visas have become radioactive.

Many in India recognize that Modi is no Vajpayee. He lacks Vajpayee’s acute appreciation of history and periodic embrace of inclusiveness. Instead, Modi is an ultra-populist who, like all populists, peddles divisiveness, conflict and fear to galvanize and reshape India. This is reflected in the BJP’s election manifesto which celebrates the alleged surgical strike in 2016 and the air strike at Balakot. The manifesto also calls for repealing both Article 370 and 35A, setting the ground for demographic change in Indian Occupied Kashmir. Both these issues impact Pakistan in the long term. A push by a re-elected Modi to change the disputed nature of Jammu and Kashmir while altering its Muslim majority nature will create even greater divisiveness, fueling the insurgency in the Valley. For Pakistan, responding to changing dynamics inside the Valley will become necessary. With a BJP that has refused to pursue the path of dialogue in Kashmir, conflict markers will likely increase. Simultaneously, India’s pursuit of punitive deterrence will impact Pakistan’s security calculus. Despite a robust conventional response by Pakistan on February 27, India’s willingness to test the escalation ladder remains undeterred. Any future engagement at the scale of Balakot retains its ability to spiral into a larger conflict between the two nuclear-armed countries.

Even a cursory flip through the BJP manifesto provides a glimpse of what the next five years of a Modi-led government will mean for Pakistan. The glaring absence of SAARC in the ‘neighbourhood first’ policy shows the BJP’s willingness to abandon South Asia’s traditional regional platform for BIMSTEC and others, sidelining Islamabad in its regional outreach. The party’s focus on pursuing multilateral platforms to push an ‘isolation’ agenda backed by a narrative of counter terrorism too is apparent. In a New Delhi run by a re-elected Modi, Pakistan’s diplomatic challenges will only increase, with dialogue remaining elusive.

Conversely, the Congress party’s manifesto banks on a more balanced approach to the region. At the minimum, it calls for a dialogue within Indian Occupied Kashmir, and lays out a regional engagement policy that recognizes the centrality of SAARC and improving bilateral relations with all neighbouring countries. What it does not do is recognize the futility of India’s military response to Pulwama.

While any realistic appreciation of the India-Pakistan relationship post Balakot will conclude that a resumption of the stalled comprehensive dialogue is unlikely in the near future, the possibilities of working towards that goal in a minus-BJP scenario is not. During the last two decades, the Congress has demonstrated its willingness to maintain, at a minimum, a modicum of sanity in this critical bilateral relationship. In the absence of political will, its pursuit of and belief in working through bilateral issues on the fringes of the comprehensive dialogue have helped stall a free fall in South Asia. Trade, visas, water, fisherman, and SAARC can steadily be brought back on the agenda with a government that does not ‘otherise’ its Muslim population, or browbeat Pakistan, for electoral popularity.

The prospects of bringing the India-Pakistan relationship back on the track of normalisation are higher without a BJP government next door. The assumptions that have underpinned the ‘hardliners can bring peace’ argument have shifted dramatically in the past decade. With growing asymmetries and decreased international interest in crisis management in South Asia, the path to dialogue rests at the door of political parties that shun populism and ultra-nationalism.