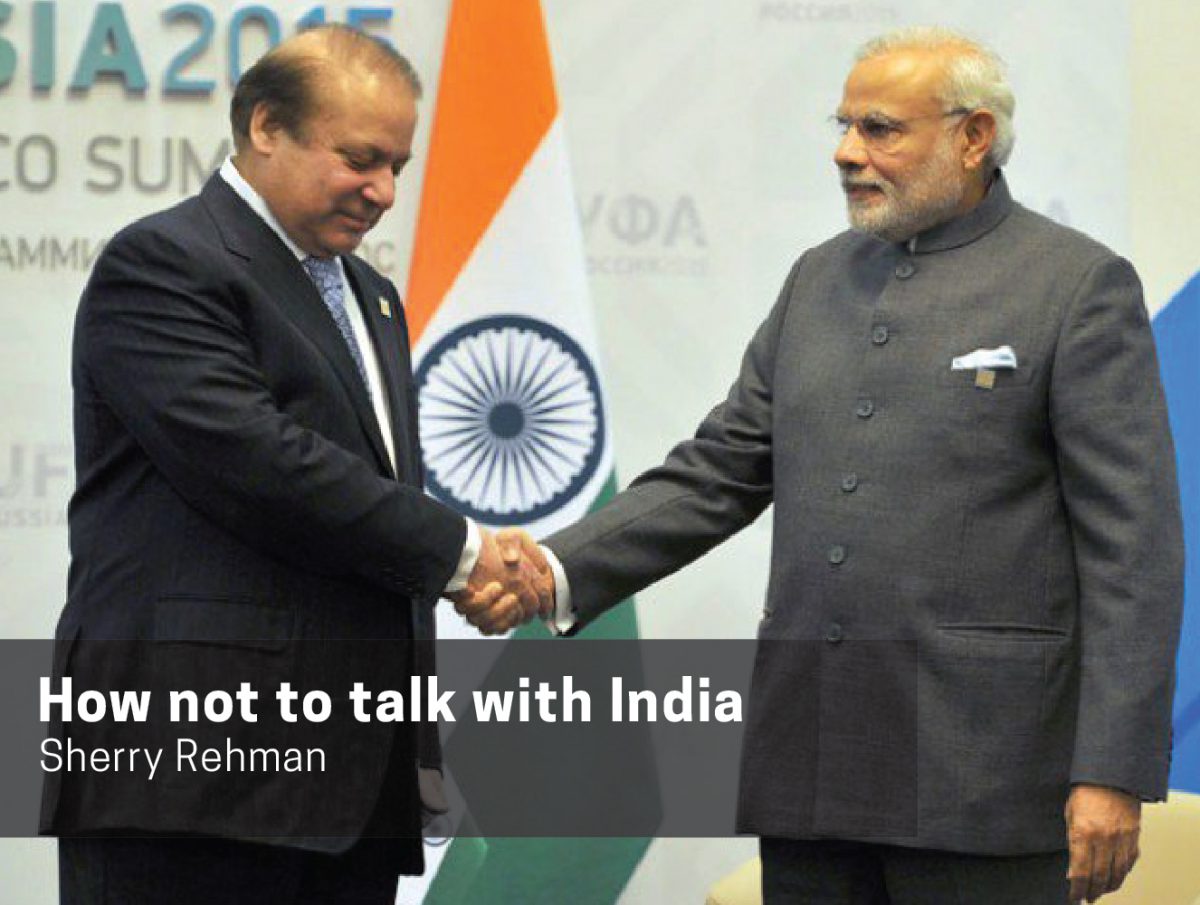

How not to talk with India

- by: Sherry Rehman

- Date: May 6, 2017

- Array

Talking to India is just as important as how not to talk.

Starting from the premise that constructive dialogue is the first step towards untangling a history of vexed relations between two nuclear neighbours, every government that has made any headway on this track has done so by first working the base at home, its politics and its message. There can be no dispute about the need for peace in the region, nor should there be any brakes on the institutional search for pathways, government or non-official, that foster sustained talks between Pakistan and India.

The recent furore in parliament about the Jindal-Sharif meeting is a case in point of poor tactics, or how not to talk. First, this case will bog down the public conversation in issues that help no government in its search for rational space between Delhi and Islamabad. Second, with due apologies to all involved, it ignores the legitimacy of the messenger. There is no dispute about the saliency of diplomacy as a quiet craft that needs the space to air ideas and test limits. In fact, the state of play between India and Pakistan desperately requires a credible back channel. Because back-channel diplomacy is often used profitably by governments in taking forward complex possibilities before they are brought on board for a public push, it is important they are conducted with credibility on both sides. If not, they land the process in flames.

Both Pakistan and India have used back-channel interlocutors in the past, but both have been institutionally appointed savants, such as Satish Lambah and Shehryar Khan, with long years of Foreign Office experience behind them, and the trust of their policy establishments. This is not to be confused with track-two diplomacy, used principally to engage between two or three countries for building confidence, exploring options, and creating knowledge about each other in stressful times. In an optimal climate, such dialogues even become invaluable in creating important constituencies for peace.

Yet even for this process which many of us invest time in, we try to keep major political parties in the loop, so that strategic conversations and the exploration of do-able options are not conducted in some policy air-lock away from public stakeholders.

When members of parliament read about a Pakistan government’s intent from Indian journalists who write about Jindal and his role as a back channel between India and Pakistan, why do we signal disquiet over this? Because back channels are useful only when the government employing them appoints one from each side, not a private business friend who obviously owes more loyalty to his country of nationality. Rumours about Jindal’s role in scuttling ripe transit-trade talks before Modi was elected don’t add comfort to the process.

Those who ignore the politics of talks with India dismiss democracy as a gratuitous parlour game. They dismiss grassroots political parties in Azad Kashmir, as did Musharraf, and they ignore the importance of institutional process, as well as its public message. They make the same mistake Sharif is making on disregarding the power of building consensus, let alone looping in its beleaguered Foreign Office. This puts not only good intent at risk, but also strategic outcomes. Such serial mis-handling is made even more poignant because while nay-sayers will say no, locking the mainstream political buy-in for talks, certainly from Pakistan is not impossible.

As a member of the leading opposition party in parliament, the PPP, I recall spurring Nawaz Sharif to accept Modi’s invitation to his inaugural on Twitter. This was no random personal statement. It was the outcome of a discussion within the party leadership about the opportunities that we hoped had arisen from a change of government in New Delhi. But most of us who consistently favour negotiations over hard stalemates were disappointed by the rush away from reason in New Delhi when all acts of terror in India were laid at Pakistan’s door.

Meanwhile, the government did Pakistan no favours by betting on silence as a tactic. When for the Pathankot attack, for instance, the Indian NIA quietly cleared Pakistan of involvement, there was silence. Explaining Pakistan, or its non-complicity in terror, was the job of Pakistan’s foreign minister, who of course did not exist except in the PM’s overstretched portfolio. But instead of advancing Pakistan’s case, and setting terms for a sustained dialogue, we saw silence.

In another layer of historical context, when Narendra Modi, swooped into the Sharif estate in Raiwind, none of us called Nawaz Sharif a traitor because we felt an elected PM must be given the confidence he deserves. Perhaps he was quietly building a foundation for sustained dialogue in private huddles with key officials, we said. But the encounter did nothing but burnish Modi’s credentials abroad, while our Foreign Office had to shrug off the much-hyped encounter as private.

In a polarised political climate where civil-military relations are already strained, and where a special assistant on foreign affairs has been made the scapegoat along with others for a PM House that functions only by close cabal, consistent non-transparency only adds to tensions and questions. For those of us who don’t subscribe to the conspiracy-theory school of politics, the issue is not that the Jindal meeting was setting the stage for another high-level one in June. There is no cavil about talks with India, in fact quite the opposite. The issue is its public message of high-level insider-opacity. If Jindal had an important message for a potential Astana sideline, he should have met Sartaj Aziz quietly. That may have been a real back channel, not publicly at PM House in Islamabad. If Modi was serious, he could have urged his NSA to start talking to our’s, plan for the worst, and leverage for the best.

So let’s not embed the optics of a Jindal-type meeting in a conversation about the importance of India-Pakistan talks. Those must go on or resume at all levels, but India too has to signal that formally. Given recent events, the summer is likely to see more human rights abuses in Kashmir after local polls in which only seven per cent of Kashmiris turned out to vote, a low not seen in 27 years. In this vitiated climate, it would be unwise to burden a potential Nawaz-Modi meeting either in Astana or in New York, with the unrealistic expectations of a dramatic reset. In public view, Modi’s government has become hostage to its own hardline rhetoric to talk on any terms but its own, so the PM might use his time better at home explaining what kind of case he will make for Pakistan abroad after skipping the Kalbhushan word at the last UNGA.

The peril of ignoring strategic context, politics or tactics is obvious. History has taught us that the substance of talks with India is as important as the optics — the way they are seen to be held, and by whom. In the end, there are three ways official talks with India will never sustain. One, when they are done under public pressure to link all talks to impossible pre-conditions. Two, the Musharraf way, in which creative solutions on Kashmir are conducted so ineptly in total lockdown that they backfire on the ground when publicly floated. Three, today the Nawaz Sharif way, all on his own, losing the mainstream political consensus for peace with India by studiously ignoring its politics in Pakistan.

Not only do such talks end in tears, but more importantly, they reverse crucial gains made earlier.

This article appeared in The Express Tribune on 06-04-2017.