The Education Landscape – Bridging Gaps

- by: Madeeha Ansari

- Date: November 29, 2013

- Array

The year 2011 was the “Year of Education” for Pakistan. The Pakistan Education Task Force, drawing upon Article 25A of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, created a sense of urgency by declaring an Education Emergency, and called upon civil society to help address the development crisis. This declaration by a body set up by the government indicated not only the extent of the challenge, but also state inability to deal with it.

Article 25A of the Constitution of Pakistan promises free and compulsory education for all children aged five to 16 – an important milestone conceding the responsibility of the state to deliver a basic right. However, in practical terms it sits in the constitutional document without much traction.

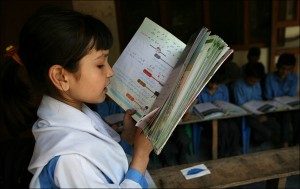

The value of basic literacy and numeracy of course is beyond dispute. In normative terms, every child deserves to be able to read. But while conceding this right is the first step, it is not, in and of itself, enough. Beyond rhetoric and legislation lies the problem of implementation. In Pakistan as in similar developing countries, the challenges of the education sector can be clustered according to issues of access, equity and quality.

As far as access in concerned, evidence suggests that universal primary education has been an elusive Millennium Development Goal for Pakistan. Currently, we have the second-highest number of out-of-school children in the world(1); there are more than seven million who should be enrolled at the primary level, while overall estimates of the number of school-age children range between 17 million and 20 million(2). Even after initial enrolment, retention and completion rates fall drastically beyond the primary level(3). The question of why this is happening is an imperative consideration for policy-makers – whether it is because of a vacuum in terms of accessible services, or because these children are forced to make an early choice between books and labour. And these are just two variables in a complex environment where choices are driven by culture, as well as the political reality of each province.

The socioeconomic conditions that determine these decisions also feed concerns about equal access to services. At present, there is no unified system of education in Pakistan. Whether or not a uniform system is a viable option is a different debate – the ground reality is that huge disparities exist in the kinds of facilities available to different target groups. Gender, income and geography all play a role in determining educational inequity; girls and the rural poor are at a particular disadvantage, and research suggests that children in different provinces do not have the same opportunities. To some extent, the private sector has stepped in to fulfill a growing demand where the government has fallen short. According to official statistics, 36% of children attend private primary schools (4).

One reason for this is the growing perception that private institutions provide better quality services. More than one research project has proven that learning outcomes for private school students are higher than for their peers in government schools. At the same time, the role of public schools in broader dissemination of education cannot be ignored and private schooling cannot be put forward as the single solution to the quality dilemma. Overall learning achievements are low nationwide, with only about 40% of children in Class Three being able to read a sentence (5).

In order to come up with practical solutions that can be taken to scale, it is important to develop an understanding of the educational landscape in Pakistan. This comprises a range of stakeholders of varying size and import. The non-government sector itself is fragmented into diverse organizations, promoting different models as “sustainable” ideas for change. However, the fact remains that even if NGOs and private institutions now occupy a sizeable chunk of the education space, the state is still the biggest and most powerful stakeholder. Government infrastructure exists where no private organizations can penetrate, even in the remote reaches of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). It then becomes a question of populating these whitewashed buildings with reliable and capable teachers.

Ideally, the resources and outreach of the government should be combined with the quality control and accountability mechanisms of the private sector. Better coordination among various actors is essential for filling the gaps that exist in the national education landscape today – whether they are research organizations, advocacy groups, international, local or community-based NGOs, provincial ministries, or the central government. This is not impossible to achieve. In the South Asia region itself, Bangladesh, has made a concerted effort to address its comparably low literacy rates. There is a clearly defined long-term strategy for advancing education which involves all stakeholders, and international organizations work closely with the government to achieve national objectives. The government has even subsidized some parts of private schooling. As a result of greater cohesion in efforts, the country has not only recorded success in terms of a Net Enrolment Rate of over 93%, but has also achieved gender parity in enrolment at the primary and secondary level (6).

Even while the problems of access and equity are being addressed, there needs to be conscious emphasis on improving quality. Each province needs to be considered in its unique context, such that provincial governments will have to adopt a proactive role in implementing Article 25A. At the same time, a standard system of capacity-building can be implemented with established benchmarks for assessing performance. The gulf between English- and Urdu-medium schools needs to be bridged through the introduction of improved curricula in the latter stream.

To try and achieve the Millennium Development Goal of universal primary education by 2015 through a single “Year of Education” was too ambitious a target. However, 2011 did manage to sensitize the nation to the gravity of the issues affecting the education sector and their long-term implications. The international community has also been roused into action and donors have recognized the benefits of investing in the social sector. Pakistan has become the largest recipient of aid from the UK, with £650 million going towards improving schools and education (7). Now that the discourse has taken a positive direction and resources have been mobilized there is, more than ever, a need to knit together efforts being undertaken in the private and public spheres.

Now is the time to formulate a shared vision and set time-bound goals for all stakeholders, to sustain the momentum of the “Year of Education”. After all, we owe it to our children.

- Pakistan Education Taskforce (2010), Education Emergency Pakistan

- SAFED (2011), Annual State of Education Report (ASER)

- SAFED (2011), Annual State of Education Report (ASER)

- Pakistan Education Taskforce (2010), Education Emergency Pakistan

- SAFED (2011), Annual State of Education Report (ASER)

- Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics (BANBEIS) (2010), Retrieved from http://www.banbeis.gov.bd/webnew/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=61&Itemid=180

- British High Commission (2011), Retreived from http://ukinpakistan.fco.gov.uk/en/about-us/working-with-pakistan/CC/education/