The Right to Public Space

- by: Sadia Khatri

- Date: September 7, 2017

- Array

My 13 year old sister and I play a game when we commute in Karachi. I count the number of men I see in public spaces, and she counts women and transgender folks. Our agreed rule is that the person must be interacting with the street in some way; walking, hanging out at a khokha, driving an open vehicle. So people sitting in cars or driving them don’t count.

Over time our playful experiment has led to an alarming ratio: for every fifteen men in public space, we see perhaps one woman. It isn’t surprising.

In Karachi, most of the women navigating public spaces are poor, there out of necessity rather than pleasure. Meanwhile, men across class do not think twice before going outside for some air, or stopping by their neighbourhood dhaba to catch up with their friends.

When it comes to women, we exist in public spaces only when we have an assigned purpose (shopping, waiting by a restaurant entrance for a Careem, commuting for a job). On the rare occasion that we are outside for pleasure – in a park, in an open restaurant, at Sea View – we are rarely alone and have our male guardians with us. Upper and middle class women are particularly adept at moving between boxes quickly. We avoid any unnecessary interactions with the street, we do not linger, we prefer the confines of our secure private cars and our expensive coffee shops.

Where are the loiterers, the walkers, the wanderers? The women who take to the streets without a purpose in mind, the ones who, like men, do not fear the city?

The politics of respectability tell me that such a woman does not exist in our world. When I express my desire to go out alone at night, my father says: girls from our kind of families don’t do that. My friends say, people will think you are a prostitute. My mother says: why don’t you take your brother along.

In each of these situations, the implication is that a woman cannot experience the city on her own terms without risking judgement or harassment. That a woman wanting to experience the city on her own terms is asking for judgement and harassment.

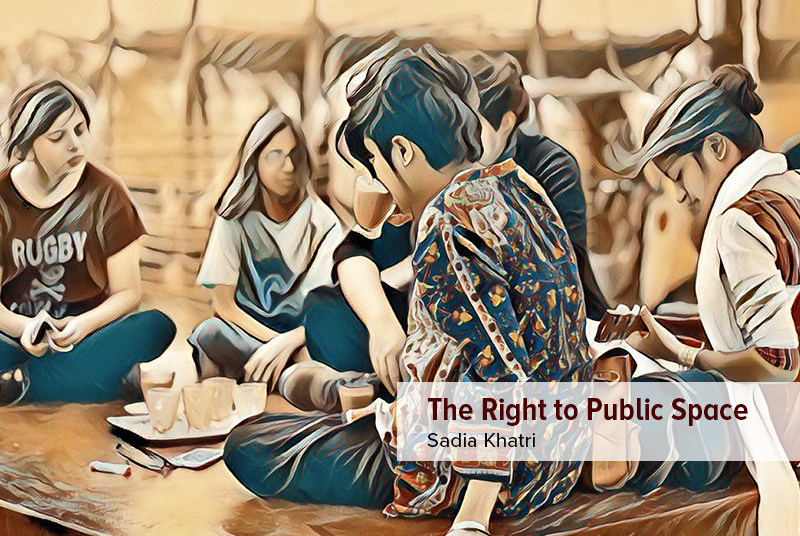

Sharing these frustrations with other women, I realized I wasn’t the only one wondering whether gender strips away one’s right to her city. A project grew organically after some of us began posting photographs of ourselves in public spaces—having chai at a dhaba, reading in a park. Women from over the country began sending in submissions, holding triumphant cups of steaming tea in the mountains, posing next to a motorbike, riding a bicycle. The project – called ‘Girls at Dhabas’ – is now a growing, real-time archive of women’s interaction with public spaces, photographs and writings chronicling our experience of the streets.

We are often told that a woman’s access to public space is a petty, trivial concern. For example, what does women’s right to sip tea on the roadside have to do with ‘bigger’ feminist concerns? In fact, everything: public spaces affect everything from our autonomy to our sanity.

In a world where women’s pleasure is dictated and curated by society, the trivial joy of roaming the city on one’s whims is a radical way of asserting control over our bodies. On a more ‘practical’ plane, financial independence is impossible without freedom of mobility, since not everyone has drivers to parcel them around. Imagine if women in Karachi and Lahore drove motorbikes, rickshaws, taxis – how many more would be earning.

But in urban Pakistan, women’s mobility is restricted and surveilled under the guise of safety. We are told to stay in private spaces with the fear that ‘something might happen to us’, a euphemism for sexual assault. While the city is built up as a site of fear, statistically, most physical violence against women is done in private spaces, by a family member or a friend. A public-private divide along gendered lines only isolates and affirms private spaces as sites of violence.

Yes, there is harassment on the streets, but Pakistani women should not clamp it down by locking themselves inside thicker walls. The incredulous looks and lecherous gazes will end only once we are a common sight on the streets, as expected as a hawker or a tree. It is important to imagine a city where this is true, where women are part of ordinary street scenes. A city where we do not side-saddle on motorbikes, we lounge on sidewalks as men do.

When my sister looks upon this city – even if it is a curated echo chamber – what changes? In this city, there are as many women on the streets as men. We are part of the streetscape, which means our presence does not meet judgement or disapproval. We do not fear the ‘common’ man, the one we are told will harass us the first chance he gets, because our safety is assumed. It can be taken for granted. In this city we do not navigate our routes out of fear; we do not worry about the length of our dupattas.

In this city we occupy dhabas and parks with the same confidence and comfort as men. We do not think twice about going down the street for a walk, or to buy a pack of cigarettes from the corner store. In this city, we define our relationship with our streets on our own terms.

But most importantly, because we are not carefully watched over, in this city we find breathing spaces, the pockets that sustain our sanity, corners for the quiet joys of doing nothing.