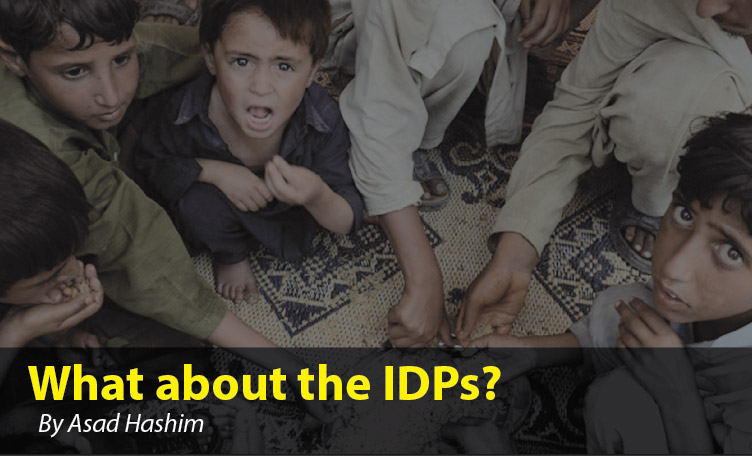

What about the IDPs?

- by: Asad Hashim

- Date: August 27, 2014

- Array

You would think automatic gunfire in a crowd of thousands would herald more of a reaction.

As the shots rang out, though, the majority of the thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) gathered around the main aid distribution point at Bannu’s sports complex remained unmoved.

They’d seen it all before, and they’d be damned if they gave up their spot in the queue – after waiting for hours, sometimes days – because police deemed the teeming mass of humanity hoping for promised government aid to be too unruly.

“They are treating humans worse than animals over here,” said Inayatullah, a 44-year-old native of Miranshah, as the shots rang out about 50m away. “They are hitting us with sticks, throwing stones at us.”

Inayatullah is one of the more than a million people to have fled North Waziristan in the wake of Operation Zarb-e-Azb, an aerial and ground offensive aimed at wiping out “terrorists of all hue and colour” in the agency, which has been a hub for the TTP, the Haqqani network, al-Qaeda and various other pro- and anti-government militias for years.

Those IDPs who reached Bannu did so after days of arduous travel. Many narrate how they were forced to walk long distances through multiple checkpoints due to the lack of vehicles or inflated rates charged by transporters. The result was tens of thousands of people being forced to undertake journeys of more than 30km by foot, in scorching temperatures of more than 40 degrees Celsius.

Most undertook that journey without food or water, getting drinking water at certain army checkpoints or from the River Tochi, which runs adjacent to the one route (the Ghulam Khan-Miranshah-Mir Ali-Bannu Road) that the military had left open out of the agency.

And those challenges were not the only thing that the IDPs were facing. The grueling nature of the journey has, by now, been well-documented: the curfews, the more than dozen army checkpoints, the queues, the lack of food and water, the babies delivered in transit, and the deaths. Persistent stories from IDPs, even those who have arrived belatedly, betray a government response to the crisis that was at best haphazard, and at worst criminally negligent. Then again, the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa government (which has been managing the IDP crisis and is on the frontlines) says that it was not told in advance about the operation, so perhaps the blame lies with the lack of communication/co-ordination between the civilian and military authorities.

Whoever was at fault, it was, as always, citizens who suffered.

Slipping through the cracks

Once the IDPs got to Bannu, conditions were not much better. Most of the more than three-quarters of a million IDPs have been staying with relatives, or crowding families of dozens into small rented rooms – rooms rented at more than three times the regular rate. Others are sleeping in schools or other government buildings, as the authorities struggle to house the massive influx of people into this sleepy little town on the periphery of Pakistan’s mainstream.

Thousands continue to throng the aid distribution points every day, waiting, on average, more than eight hours to be allowed entry.

At the distribution camps, IDPs are given, on production of an NIC and an IDP registration chit given to them at the Saidgi checkpoint, basic food supplies and a cash grant. The food supplies include 4kg of daal, 80kg of wheat flour, 4.5 kg of cooking oil, 1kg of salt and 30 high-energy biscuit packets.

A cash grant of Rs12,000 per family is also disbursed (in the form of a one-time payment of Rs5,000 and a monthly stipend of Rs7,000).

But there were problems in disbursing the funds, IDPs say, with aid workers saying that certain funds have yet to be released, holding up their disbursal to the IDPs. In addition to those delays, there are plenty of people who are slipping through the cracks due to lack of identification papers or bureaucratic mix ups. One widow, a mother of nine from Mir Ali, told me she had been denied government aid because she did not have an NIC, having always relied on her late husband’s ID card for her infrequent brushes with the bureaucracy in North Waziristan.

Bannu, meanwhile, continues to struggle to cope with the massive influx of people into a town that finds it difficult to deal, in terms of infrastructure, with even its existing population of about a million people. At the moment, one out of every two people in Bannu is an IDP, and the town appears to be choking on them.

The fact that other provinces have been less than forthcoming in their aid towards IDPs does not help. The single government-run IDP camp, set up in the under-curfew area of Bakkakhel in FR Bannu, remains empty, despite being well resourced. IDPs say they are staying away because of “reasons of tradition” (referring to the inability to maintain ‘purdah’ in a camp), but also due to threats made by the TTP before they fled.

More significant than the threats or “cultural reasons”, however, may be the location of the camp: Bakkakhel is about 10km outside of Bannu, in Frontier Region Bannu. The area is under a 24-hour curfew, and with military operations ongoing, it is also isolated from the main city. There are no active markets or other facilities in the area. Those handful of IDPs who are staying at the camp say they were only doing so because they could not afford to stay in the town. While the camp is well-resourced and secure, it is also little more than a de facto prison for those IDPs who choose to avail its facilities.

Meanwhile, the army has launched a ground offensive in North Waziristan, insisting that while it is endeavoring to keep collateral damage to a minimum, it is now ready to move the fight into settled areas.

The FDMA says that more than one million of the agency’s residents have been registered as having fled but locals told me that many have stayed behind: the old, the infirm and those who were either unable or unwilling to take the journey to Bannu.

As aid efforts continue to kick into overdrive, with more than 50 collection points set up all over the country and more than Rs13 million and 276 tons of rations already donated by citizens to the cause, it may be worth sparing a thought for those who have continued to remain behind, who never became ‘internally displaced’.

With scant attention being paid to the plight of IDPs, the government needs to urgently refocus attention towards a crisis that may well become a humanitarian disaster. The following policy recommendations could help the government formulate a holistic response to the IDP crisis:

– Relocate the Bakkakhel camp to an area that is closer to the settled area of Bannu. The camp is only home to about 340 people, so while this will be an initial discomfort, it will also ensure the twin outcomes of more IDPs receiving aid, and less resources being wasted.

– The management of IDPs is currently being carried out, in parallel, by the FDMA, the KPK government, the military and the NDMA, who has sought the informal help of the UN. These agencies are co-operating, but in a space that is unclear. All stakeholders should be brought on board to a single plan, with clear areas of responsibility, accountability and authority.

– A broad timeline for the military operation and the duration of the IDP’s displacement must be shared with both relief agencies and IDPs. Currently, both are operating under an open-ended timeline assumption, which retards the ability to meet relief needs, and breeds greater uncertainty.

– Other provinces must immediately officially open their borders to IDPs from Operation Zarb-e-Azb. Bannu cannot continue to absorb the weight of the displaced population, and it erodes national unity for distinctions to be made between citizens based on origin.

– The process for registration and aid disbursal must be made clear to IDPs through an information campaign. Many continue to be confused as to what the process is, and what they are entitled to. Information counters and a campaign involving pamphlets and radio spots can help alleviate this problem.

Asad Hashim is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad, primarily working as Al Jazeera English’s Web Correspondent for Pakistan. He tweets @AsadHashim.