Where Do India and Pakistan Go From Here

- by: Fahd Humayun

- Date: March 28, 2019

- Array

For a region that until a month ago was on a collision course for war, India’s decision to boycott Pakistan Day celebrations at the Pakistani High Commission in New Delhi last weekend came as no surprise.

An extraordinary air duel in February brought the two sides unthinkably close to a nuclear winter, and with it ugly memories of the last major India-Pakistan conflict.

Getting the dust to settle hasn’t been easy; it is still not clear whether the confrontation’s exit wounds will fade or fester. Both sides have vacated border villages. Artillery continues to be fired across the Line of Control. Defense systems remain on high alert. Wartime deployments are ongoing. At any given moment, India and Pakistan have a combined total of 300 nuclear warheads pointed at each other. India’s national air carrier has clubbed Europe and US-bound flights on account of the closure of Pakistan’s airspace.

A meeting that was supposed to take place in New Delhi to discuss modalities for the Kartarpur land corridor for pilgrims two weeks ago was downsized by India to a one-day interaction at the border.

Since 2015, both states have avoided full-on conflict, partly by absorbing smaller but still bloody skirmishes along the Line of Control.

But an active insurrection in Indian-Occupied Kashmir has stoked cross-border tensions and provoked a heavy-handed crackdown by the Indian state.

By contrast, Islamabad’s measured tone has been an uncharacteristic foil to the jingoistic fervor of Indian hawks in the weeks that followed a deadly suicide attack in the Pulwama district of Indian-held Kashmir. This month, state authorities in Pakistan undertook a number of arrests and asset seizures, the most sweeping in years, as part of a campaign against banned militant organisations.

India’s election is still a month away, and the potential for crisis hangs over South Asia like a thick plume.

Since 2014, India’s lurch towards ultra-nationalism has depopularized the idea of strategic restraint, and made war a catchy sell.

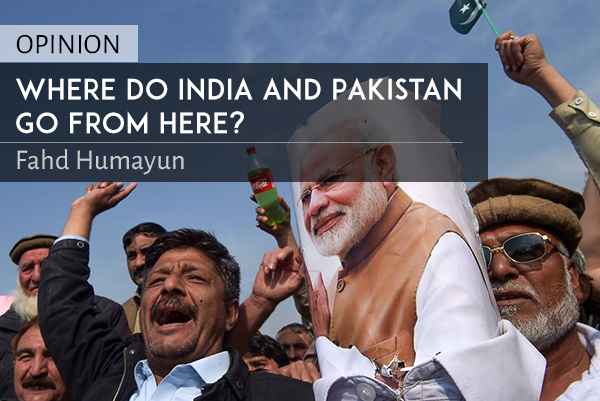

Next month’s election, which will see 900 million Indians go to the polls, is expected to be a referendum on Mr. Modi. But in Pakistan, the choice that Indian voters make will also potentially signal the Indian public’s bandwidth for bilateral engagement and the possibility of resuming a comprehensive dialogue after May. So far, much of Mr. Modi’s rhetoric has painted Pakistan less as a strategic opponent, and more as a threat to civilization.

Mr. Modi, once persona non-grata in the West, has also sought to offset impressions of economic impotency at home by subscribing to chauvinistic muscle-flex and military exhibitionism. Last September, India held a mega celebration to mark two years since its so-called surgical strikes, in which it alleged Indian soldiers had crossed the LOC to teach Pakistan a lesson. Pakistan denies the incident ever took place.

The hyper-nationalism of the Modi government contrasts with the ‘Vajpayee route’ of seeking eventual normalisation with Pakistan.

The former BJP Prime Minister, who died last October, made unprecedented diplomatic breakthroughs with Pakistan, including launching a Delhi-Lahore bus service, and bringing actors, writers and cricketers with him when he travelled to Pakistan. On the announcement of his death last year, Pakistan’s Foreign Office tweeted an Urdu couplet that the former Indian PM had recited on his Lahore visit beginning with the words “I won’t allow another war”.

The Vajpayee vision contrasts with the high-octane discourse of a shrill and heavily corporatised Indian media today that makes coercive diplomacy attractive, and costly wars look profitable. Indian cricketers recently came under scrutiny for “militarizing” the game after its players wore army camouflage caps during a match against Australia. Pakistan has confirmed it will not be airing Indian Premier League (IPL) 2019 matches.

Such tactics, emotive as they are, make it difficult to predict whether political elites will be successful in marshaling public opinion in India towards a strong centrist-course correction, or indeed if India and Pakistan can manage to parlay the goodwill from their recent Kartarpur meeting into more substantive confidence-building. There is little in the way of cross-border commerce between the two countries. Visas are notoriously hard to come by. Symbols invite havoc: last summer, India’s Aligarh Muslim University was stormed by an armed group of Hindutva nationalists who demanded that a portrait of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, which had been hanging in the university for almost 80 years, be taken down.

Unsurprisingly, many in Pakistan see Mr. Modi’s government’s glossy brand of internationalism as a mask for the religious zealotry at home that has direct consequences for bilateral relations. The acquittal of four of the accused in the 2007 Samjhauta Express terrorist attack by a special Indian court is a case in point. The attack, which was carried out by the rightwing Hindu RSS, killed 68 people, at least 43 of who were Pakistanis.

So far, India has indicated it would like to retain, rather than revise, the bilateral deep-freeze. But it is clear such a strategy is both dangerous and untenable. Without deeper, institutionalized layers of engagement, escalatory dust-ups, such as those that followed in the wake of the suicide attack in Pulwama district, will continue to imperil regional stability.

While India is aided by satellite imagery about Pakistani troop movements, each side’s threshold for escalation remains dangerously opaque. During the 2001-2002 standoff following a terrorist attack on the parliament in New Delhi, both sides were still learning and adjusting to their respective levels of risk-appetite.

This February, many of those early myths of strategic restraint were shattered by the hyper reality of live aerial combat. At the peak of the February crisis, TV anchors in India dressed in military uniforms. Expressways in Pakistan’s key cities of Lahore and Peshawar were closed for traffic to enable fighter aircraft to land if needed.

To avoid uncontrolled escalation, at some point both sides will have to backstop the relationship with more effective crisis-management mechanisms. Ideally, this should include the institutionalization of an effective backchannel, which saved the relationship from collapsing after the Pathankot attack in 2016.

Practically speaking, such measures are unlikely until India is on the other side of a critical, and deeply polarizing election, and the BJP stops using Pakistan as a dog-whistle to target anti-nationalism.

But some Pakistanis legitimately worry that, if re-elected, a hyper-focused Modi government may notch up tensions even further, starting with renewed violence in Kashmir, and plummeting the region into a frustrating arc of known unknowns. Which is really just shorthand for more brinkmanship.

A version of this article appeared in Foreign Policy on 27-03-2019.